What if the last true freedom in language wasn’t in poetry, or code, or literature—but in Gwaffiti? As artificial intelligence continues to harvest every commercially viable expression of human language, it’s becoming harder to tell where the human ends and the algorithm begins. And yet, style writing—Gwaffiti’s most cryptic and idiosyncratic branch—seems to resist. It’s underground, illegal, romantic, but most of all because its language is simply too complex, too local, too weird to be easily decoded.

This essay traces a fragmented, trans-European story of letterforms, subcultures, and cultural backchannels. From the NYC mid-’70s roots to the squats of Berlin, from tomato cultivars to Milanese orthodoxies, we follow the erratic, stubborn growth of style—untranslated, and sometimes untranslatable.

It’s about punk, politics, zines, and spray paint. About how ideas travel by train. And about how a few obscure aesthetics may outlive the machine. Let’s begin where things still can’t be indexed.

AI and the Last Language Standing

If we look 100 years into the future—assuming we’re still around on Planet Earth—one thing seems certain: AI will have extracted every last commercially useful drop from human language.

Only style writing—Gwaffiti’s most intricate and self-referential form—will retain some intellectual freedom from corporations and machines, thanks to the sheer complexity of its visual language.

By then, legions of academics and freshly minted PhDs will flock to study wild styles and softies (those iconic bubble letters). Linguistics will go through a renaissance, and veteran writers will launch billion-dollar consulting firms to help the broader public grasp the inner mechanics of style. Luckily, we still have a little time before AI learns to decode the ineffable.

Know Your Enemy: Linguistics and Other Oddities

As writers, it’s wise to know your enemy—and that means diving into the basics of linguistics as soon as possible.

Don’t worry, language studies are full of bizarre gems and mind-bending factoids: you’ll have fun along the way. Take the Nivkh language, for instance: a linguistic relic with no proven ties to any known language family, possibly dating back to late Pleistocene hunter-gatherers. Or the Appalachian dialect, so eccentric and archaic that it’s become a kind of mythical creature—half real, half urban legend in the world of linguistics.

For centuries, comparative linguistics also entertained some wildly speculative theories. Joseph de Guignes once claimed that China was a colony of Egypt. And Jean-Pierre Brisset, in his delightfully unhinged La Grande Nouvelle (1900), argued that humans descended from frogs—his proof? A comparison between human speech and frog croaks. But hey, with outlines, maybe we’ll soon be able to talk to our cats too.

Tomatoes, Cultivars, and Letterforms

Most of the time, as Charles Darwin observed, languages behave like plants: they grow, evolve, hybridize, go wild, or disappear. The same goes for aerosol writing styles—they have lifespans, spread across regions, and sometimes remain beautifully local or unexpectedly viral.

Take tomatoes, for example: they arrived in Europe in the early 16th century under their original Nahuatl name. Today, there are dozens of varieties with poetic regional names—Muchamiel, Scatolone di Bolsena, Karampola, Téton de Vénus. Why not treat Gwaffiti styles the same way?

The NYC mid-’70s classic could become the Mostruoso de Roma of the Italian capital of the ’90s subway bombing. Skeme and CIA-inspired lettering might be renamed Dutch Forever—that immortal Amsterdam style of the mid-’80s. It’s time to get creative with taxonomy. Maybe what we really need is a hybrid profession: part botanist, part linguist, specialized in hip hop genetics.

From the edge of the map—say, Milan—it offers a pretty compelling way to trace the tangled roots of European style writing. Let’s dig in.

Before Street Art: Seeds Across Europe

Let’s go back to the early names in the history of French wall-based art: Ernest Pignon-Ernest, born in 1942, a Fluxus- and Situationist-influenced artist, and Daniel Buren, with his Affichages Sauvages in the early 1970s. Both were trained artists who didn’t need a sociologist to explain what was going on in the NYC subways—they simply picked up on the vibe and started doing similar things in the streets of Paris.

Meanwhile, in Florence, the satirical magazine Ca Balà’s cartoonish logo—created by Graziano Braschi of Gruppo Stanza—was turned by the author into a stencil for public use as early as 1971. This was the aftershock of the ’68 protests blending with traditional artistic practice. Aroldo Marinai, a close friend of Gruppo Stanza, has recently been rediscovered by Isabel Carrasco Castro as the author of one of the earliest known street interventions in Italy: his Frogmen stencil and 1979 book (recently reprinted) mark a fascinating and underexplored chapter in this story.

Of course, people in the know will insist: “This isn’t street art.” Maybe not. But it’s still fascinating—and fun—to see the same kinds of gestures emerging independently across Europe, unaware of each other, like parallel seeds sprouting in different soils.

Punks, Rats, and the Writing Code

If you dig into the early history of writing in Paris and Amsterdam, it’s punk that comes up first. Amsterdam on Tour, the book by Dutch old-timer Again, offers a meticulous archive of this short-lived but intensely hardcore scene. In France, names like Blek le Rat, Miss Tic, and Jef Aérosol are now widely recognized. In Italy, early movers such as Giacomo Spazio, Tommaso Tozzi and Abele or Paolo Dolfini a.k.a. Cerebro Fritto emerged from a strange but potent mix of punk, avant-garde, and new wave.

Many Milan punks traveled north—to Berlin, Amsterdam, Paris—and returned with spray cans in hand, ready to start writing. Our own founding fathers were Atomo and Swarz, together with our first lady writer, Shah.

By the early ’80s, the punk wave of ’77 had mostly faded in Northern Europe. But that timing worked in Italy’s favor: when Atomo and Swarz began painting in ’83, they did so within a more stable militant squat infrastructure that helped preserve and transmit knowledge. In the late ’80s, they passed the flame to a new generation.

The codes were already set: if Amsterdam had a Dr. Rat and every squat in Berlin had a pet rat, why change anything in our local neighborhoods of Lambrate and Porta Ticinese? Meanwhile, punk itself had evolved. Hardcore was taking over, skating had become the new gateway to graffiti. Dante Ross captured this shift perfectly in his brilliant essay, The Rise of the Punk Rock B-Boy. The same was happening all over Milan at the time.

Stalingrad, Spraycan Art, and Style Sync

Most would agree that the first major Hall of Fame in Europe was Stalingrad, in Paris. It quickly became a key point of contact for hip hop culture across the continent—especially for b-boys from Milan, who were already connected to the Paris scene in the early ’80s.

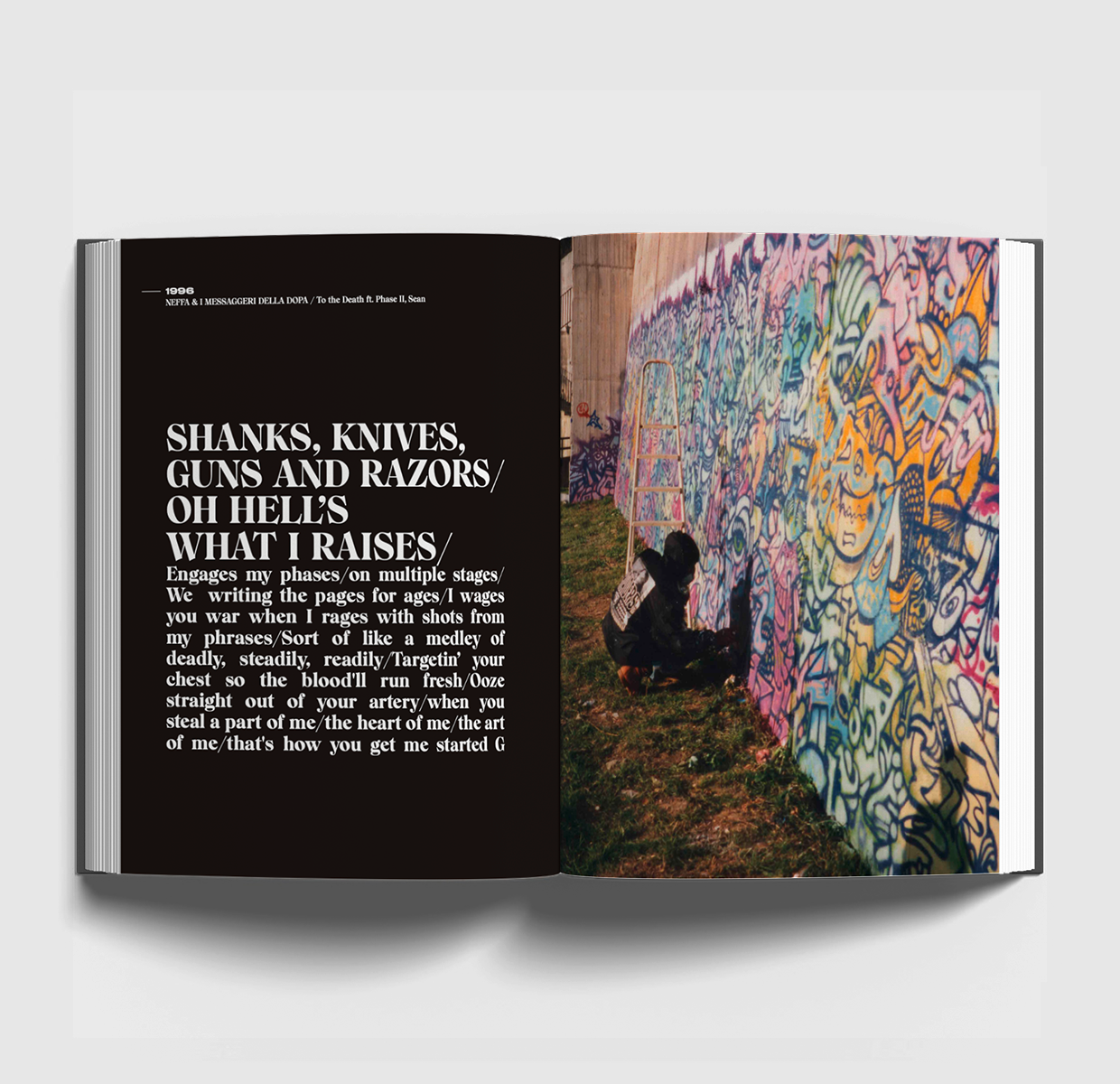

At the same time, Milan held a unique position: both as a hub for the booming art market and as a landing spot for the early graffiti wave. Artists like Phase 2, Rammellzee, Basquiat, A-One, and Sharp all passed through or lived there for extended periods during the early to mid-1980s. The show and catalogue Arte di Frontiera is a testament to that era. The weight of Phase 2’s Italian legacy has only recently been documented, in Kill Tha G Word: The Italian Years of P.H.A.S.E. 2, a major publication by Maurizio d’Apollo.

When Spraycan Art dropped in 1987, it hit like a reset button. Writers in Milan began absorbing the styles featured in the book—above all, the influence of Stalingrad’s TCA crew was unmistakable. For many local scenes, Spraycan Art became a bible: a universal entry point for beginners and a stylistic reference across continents. It’s easy to forget now, in the age of Instagram and algorithmic feeds, how radical that kind of global synchronization once was. But back then, Spraycan Art marked the first real wave of stylistic homogenization in Gwaffiti—a moment when letterforms began to speak the same language, everywhere.

Spyder7, Munich, and Milanese Orthodoxy

There was one major omission in Spraycan Art: the Munich scene. And yet, for northern Italian writers, Munich was the closest international Hall of Fame you could reach by train. Its styles quickly became a visual reference, thanks to visits from Dayaki in Bologna and the MCA crew in Milan. At the time, On the Run magazine was also circulating. Its raw, angular aesthetics had a lasting impact—between 1989 and 1992, that Munich style shaped both bombing and Hall of Fame productions across Italy.

Munich itself drew early influence from the Stalingrad school of style. As for smaller cities, they usually took the path of least resistance—following whatever style signal was strongest. Often, that meant aligning with a powerful local crew whose visual identity became a cornerstone for others, helping establish a kind of shared, transnational language of style.

By then, Milan had developed into a surprisingly diverse village of a few hundred writers, loosely structured into stylistic factions:

– TCA with an Amsterdam flavor

– TCA with a Munich edge

– Bold abstract styles inspired by Spraycan Art

– Punk-infused pieces

– And one particularly orthodox NYC-style current

That last one stood apart from any European influence. It stemmed from the pioneering work of Spyder7, a lone wolf whose devotion to NYC-style softies and bars’n’arrows laid the foundation for a cult-like school of writing. Active since around 1987, Spyder7’s and the Pals With Dreams approach peaked in visibility during the golden years of national hip hop zines, around 1993–94. He preached aesthetic separatism with near-religious fervor:

“Never mingle with practitioners of European styles. They are inferior, corrupted, and worthless.”

Extreme? Sure. But in retrospect, that radical stance helped Milan develop a scene widely recognized for its sophistication and distinctive voice.

Paris Tonkar and the Era of Exchange

For most writers, the next major revolution came in the form of another seminal book. Since Spraycan Art hit in ’87, times had changed—and Paris Tonkar landed like a lightning bolt, shaking up those who had grown a bit too comfortable with traditional styles.

At first, the shock took time to register. But soon enough, things started moving fast. Some writers, like Lemon, seized the opportunity to scrap everything and start over from scratch. Others—like the LHP crew—joined forces with Mambo from La Force Alphabetik, channeling the energy of hip hop into the legacy of ’70s political activism. Their stylistic language was laser-focused, almost eerie in how precisely it reflected that historical moment: comrades armed with spray cans.

Meanwhile, new connections were forming with scenes in Paris and the Netherlands. The regional train system became a fresh playground by ’94, as captured in the iconic picture book FNDAMENTALE 1992–2002. Names like Ces, Opak/Soleil, Jon, Sharp, and Bates became part of a fast-moving exchange of styles and ideas. Zines circulated at lightning speed. Writers met face-to-face. The modern era of European style writing had officially begun.

Conclusion

Style writing was never meant to be preserved. It wasn’t created for museums, biennales, or search engines. It emerged from urgency, coded speech, and the need to mark space with something unmistakably personal. And yet, across the last fifty years, it has developed its own deep history—full of migrations, misinterpretations, underground myths and improbable genealogies.

Maybe AI will one day catch up. Maybe it won’t. Until the Superintelligent AI riddle is solved, handwriting is one last bastion of humanity. Hey, you don’t even have to be literate to understand aerosol art, it’s gut instinct and AI has no algorithm for that.

Shadrack

*: When asked why he prefers to use the word Gwaffiti instead of the more common term, the author of this article replied: « Phase2 taught us a lot in the early Nineties and his motto Kill the G word stuck with us. He sometimes used the word Gwaffiti, with a French sounding R mocking art gallery types. It’s a long time ago but his ideas are still valuable. »

Publisher’s Note: If you enjoyed this article by Shadrack, we highly recommend checking out his other publications — including Trap magazine (issue 1, issue 2, and issue 3), originally released in the early ’90s and recently reprinted. Also worth exploring are the Book Hand Style by Phato CKC and the art book Bangsta CKC.

And don’t miss Pezzate Passate. It’s in Italian blog, but easily translatable.