From the very beginning, graffiti and street art—like most urban subcultures—have been about occupying space. Tag after tag, piece after piece, wholecar after wholecar, the ambition has always been the same: to inscribe a name and a style into the city itself. Being “all city” was never a metaphor; it was a concrete objective.

In 1970s New York, the scale of the playground made this ambition plausible. Nearly eight million inhabitants, more than 1,200 square kilometres, and a city going through deep social and economic crisis—the same crisis that would later inspire Milton Glaser’s iconic I ❤️ NY campaign. It was a perfect breeding ground for graffiti, even if Mayor Ed Koch never really saw it that way.

But what happens when the context is the exact opposite?

What if the city is extremely small, geographically constrained, permanently overcrowded, and shaped almost entirely by real estate pressure and private property management?

This is not a dystopian scenario or a post-apocalyptic fiction. It is Malé, the capital of the Maldives. Known worldwide for its turquoise waters, coral reefs, and luxury resorts—one of the most iconic honeymoon destinations on the planet—yet rarely associated with graffiti or street art.

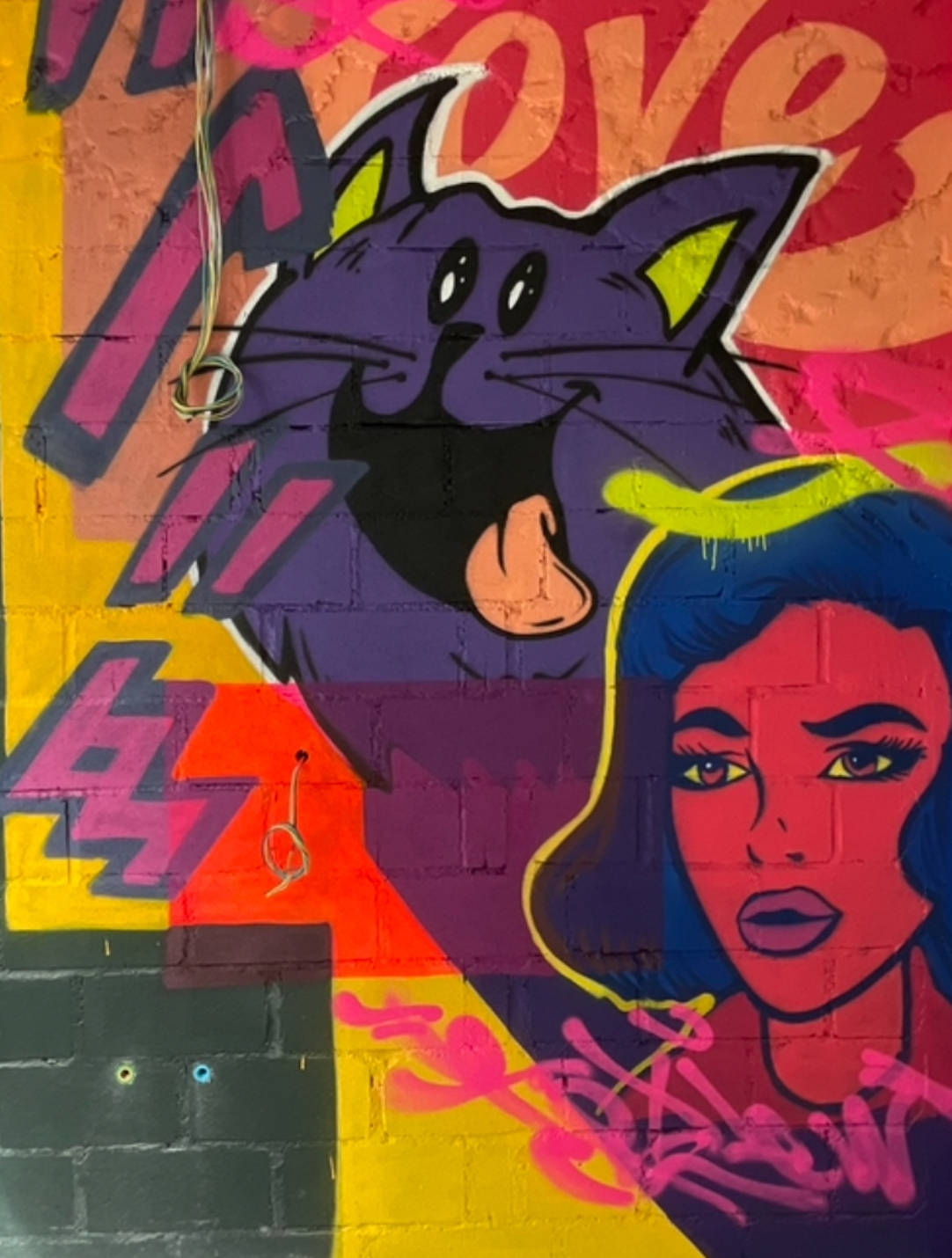

To understand how urban expression can exist in such a place, we spoke with Toxi, one of the key figures of street art in the Maldives. His perspective offers a rare insight into what it means to paint in a city where space itself is the main obstacle.

Boxir: Hi Toxi, good to speak with you again. Could you briefly introduce yourself and tell us how you first got into graffiti and street art in Malé? When did you start, and how did you come into contact with this culture? Were there writers before your generation?

Toxi: Hello Boxir, it’s a pleasure to connect with someone who shares the same passion. Thank you for the opportunity.

I was born and raised in Malé City. Around the age of twelve or thirteen, I began painting on walls—though not yet on the streets. These early murals were made for school projects, birthday parties, and ceremonial events. Even then, I was drawn to working on a large scale. Spray paint appealed to me because it allowed speed and control; it felt intuitive.

For a long time, my painting stayed within these informal but accepted spaces. That changed when I met a friend who suggested we take our work outside and try graffiti. Until then, painting in the streets hadn’t fully taken shape in my mind, but his encouragement opened that door completely.

That friend, Mo, was the one who really pushed me to take it to the streets. I remember writing “Raalhu Rules” in the city’s surf area—street slang meaning “waves rule.” Just three days later, a massive tsunami struck the Maldives. This was in 2004, and the moment remains deeply etched in my memory.

From there, things slowly evolved. I began seeing more tags and some solid pieces. There were writers and even stencils appearing. Back then, it was me, Lick, and 2dark.

We weren’t the first—there were already traces of writing scattered around the city, mostly territorial markings left by street gangs. But for us, this was something entirely new, formative, and driven by a different intention.

Boxir: Malé covers less than 6 km² and hosts around 100,000 people. You can cross the island in about twenty minutes, surrounded by constant traffic and ongoing construction. In such a compressed and saturated environment, how do you find space—and opportunities—to paint? Is painting always a form of negotiation here?

Toxi: Space for graffiti has always been extremely limited, constrained by constant surveillance, strict regulations, and the nonstop flow of people. Despite this, we managed to find a few permitted walls where we could work openly and let the art exist in public space.

Over the years, I also organized several competitions in collaboration with an NGO focused on raising awareness against narcotics. I didn’t paint myself during these events; instead, I created opportunities for the public to participate. The response was overwhelming, and these initiatives continued for several years, helping to engage the community and nurture local creativity.

Here, you often have to create your own opportunities to create. Graffiti has also been used for promotional purposes—adopted by major corporations as a marketing tool, and even by the Ministry of Youth. These projects made it possible to earn from the work, allowing the practice to sustain itself while still leaving room for artistic expression.

Boxir: Despite these constraints, some places seem to function as informal cultural hubs—Comfood, for example, or community-driven spots like the surf city area and Hulhumalé beach. How important are these spaces for maintaining a local creative community?

Toxi: Around the same time graffiti began taking shape here, skateboarding emerged alongside it. The two cultures arrived almost simultaneously, feeding off the same energy and sense of freedom. I remember skating with friends and always carrying a few spray cans with me, ready to paint whenever the moment felt right.

The two practices naturally intertwined—both offering movement, expression, and an alternative way to claim space in the city.

The few places that supported art and youth culture became incredibly important. They acted as rare safe zones where creativity could exist, friendships could form, and ideas could grow. These hubs didn’t just support artistic practice; they fostered community and played a meaningful role in artistic development and mental well-being.

Boxir: In a city where space is scarce and tightly controlled, painting in public can easily take on a political dimension. Some of your works engage directly with social or political issues. Do you see street art in Malé as an inherently political act?

Toxi: In the early 2000s, the Maldives was going through a period of social and political turmoil. During that time, graffiti became a powerful form of expression and played a visible role in the events leading up to the political shift in 2008.

That said, I don’t think graffiti took root here only because of politics. It endured because of the beauty and color it brings to the city. More than protest, it reflects an evolving culture and gives voice to people living in the present moment. At its core, it is art.

Boxir: The Maldivian economy is largely driven by tourism, and most art commissions and exhibitions are tied to resorts and hotels. How do you navigate this reality as an artist? Is there a tension between producing work for tourists and addressing a local audience?

Toxi: Being an artist here is challenging. The population is small, and the local art market is limited. Opportunities to sell work are rare, which means adapting and finding ways to sustain a practice.

Over the years, I’ve taken on many commercial mural projects—working with corporations, hotels, and resorts. These projects make it possible to continue creating.

But it’s when I create for a local audience that my identity feels most visible and honest. Those works carry a different weight. They speak directly to the place and people that shaped me, and they have deeply influenced how I define myself as an artist.

Boxir: To wrap up, could you tell us about any upcoming projects or ideas you’re currently working on?

Toxi: The year has started slowly, but I’m planning and developing new projects. There are a few exciting ideas in progress, including an upcoming exhibition and projects on several local islands later this year. I’m especially looking forward to traveling and seeing where the work leads. I’ll be sharing updates on Instagram.

Boxir: Thanks a lot for sharing your experience. If you have any advice for people visiting the Maldives—especially those curious about Malé beyond the resorts—feel free to share it.

Toxi: Thank you, Boxir. I really enjoyed working on this piece together and hearing your experiences—it meant a lot.

To the readers: come visit the Maldives. Walk through Malé, explore nearby local islands, and experience everyday life beyond the resorts. Spend time with locals and discover their traditions. And to fellow artists—we’ve got good cans here: Montana Gold, MTN, and Rusto. Just bring your caps.

Follow Toxi & Explore More