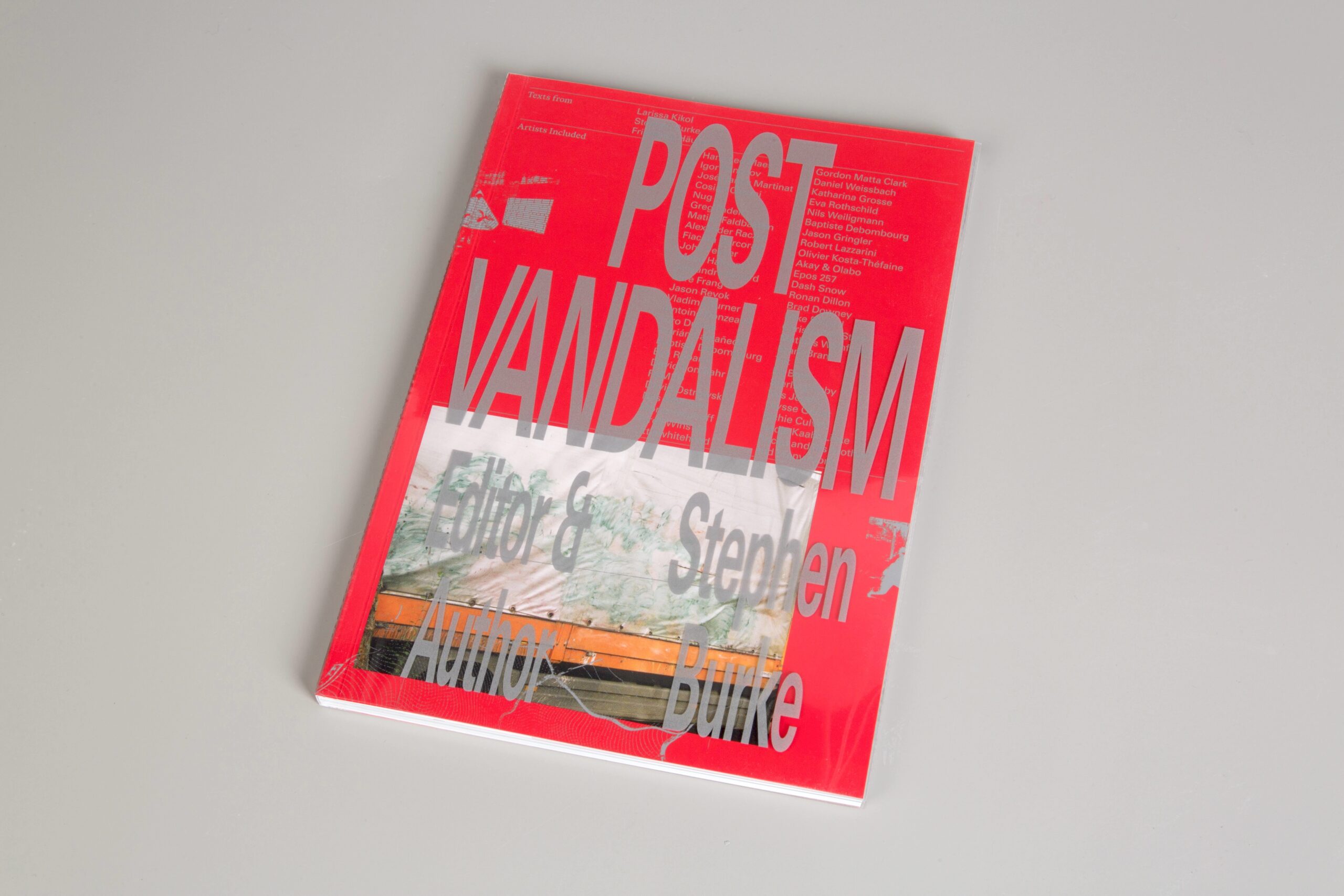

The release of Post Vandalism — Stephen Burke’s new book exploring the thin line between art, intervention and urban disorder — marks an important moment for anyone following the shifting borders between graffiti, public space, and contemporary art. To coincide with the publication, Andrea Ceresa — one of the most incisive critics of his generation — sat down with Burke — artist, archivist and founder of the Post Vandalism platform — to discuss the origins of the concept, the subcultural instincts behind it, and the way certain gestures move from the street into the studio without losing their raw energy.

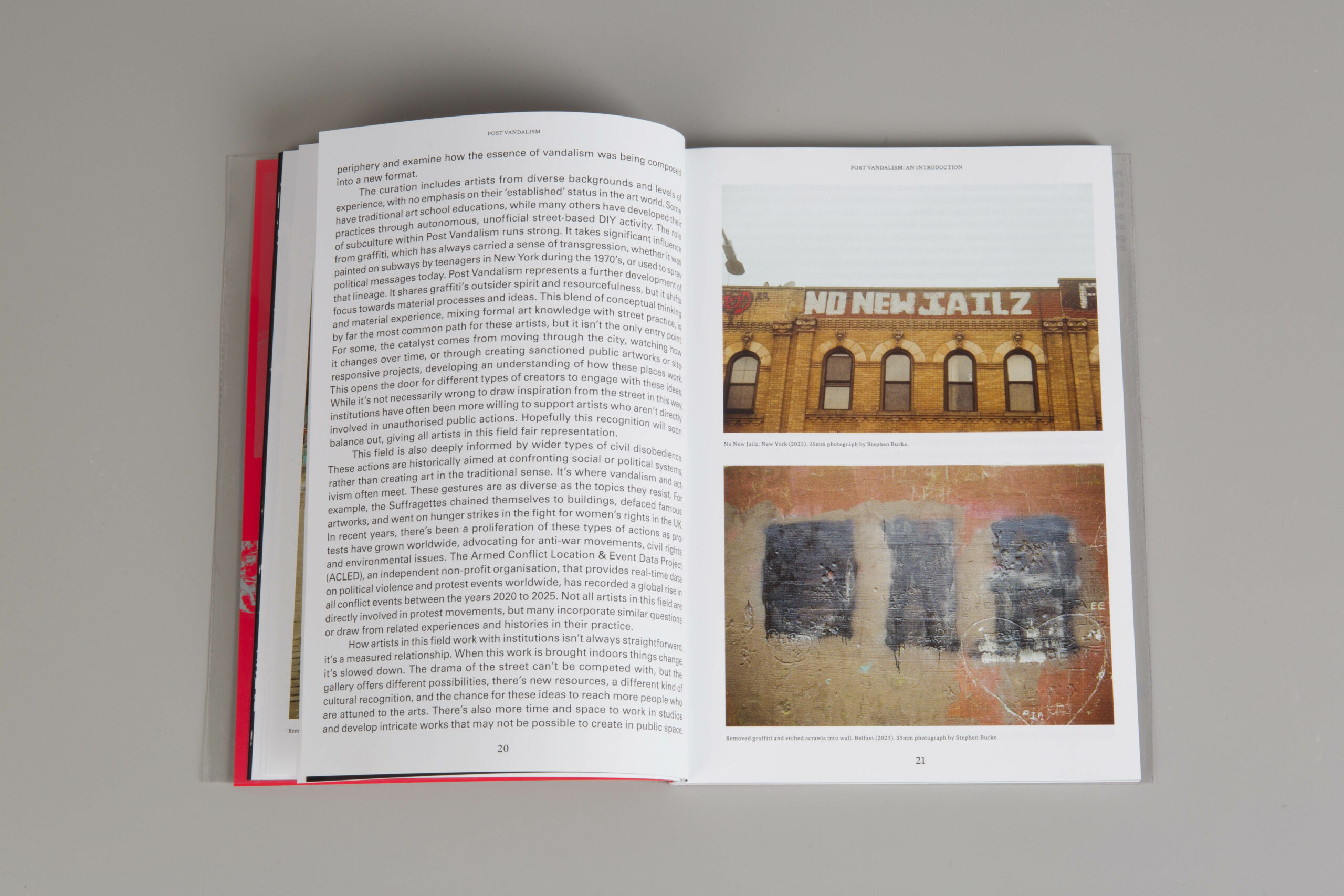

Far from being a formal movement, Post Vandalism is best understood as a field of practices shaped by urban experience, DIY knowledge, and the material reality of cities. It draws on a long history of “damage-to-create” approaches in art, while staying firmly rooted in the informal, improvised culture of the street. In this conversation, Burke reflects on how environments like Dublin, Glasgow, Berlin and Prague have influenced his perspective, why certain works resonate beyond their initial context, and how he uses the Post Vandalism archive to document a rapidly evolving landscape.

Andrea Ceresa (AC): I think graffiti is the greatest example of this dichotomy of art and vandalism. Was it an important reference for you in the creation of the concept?

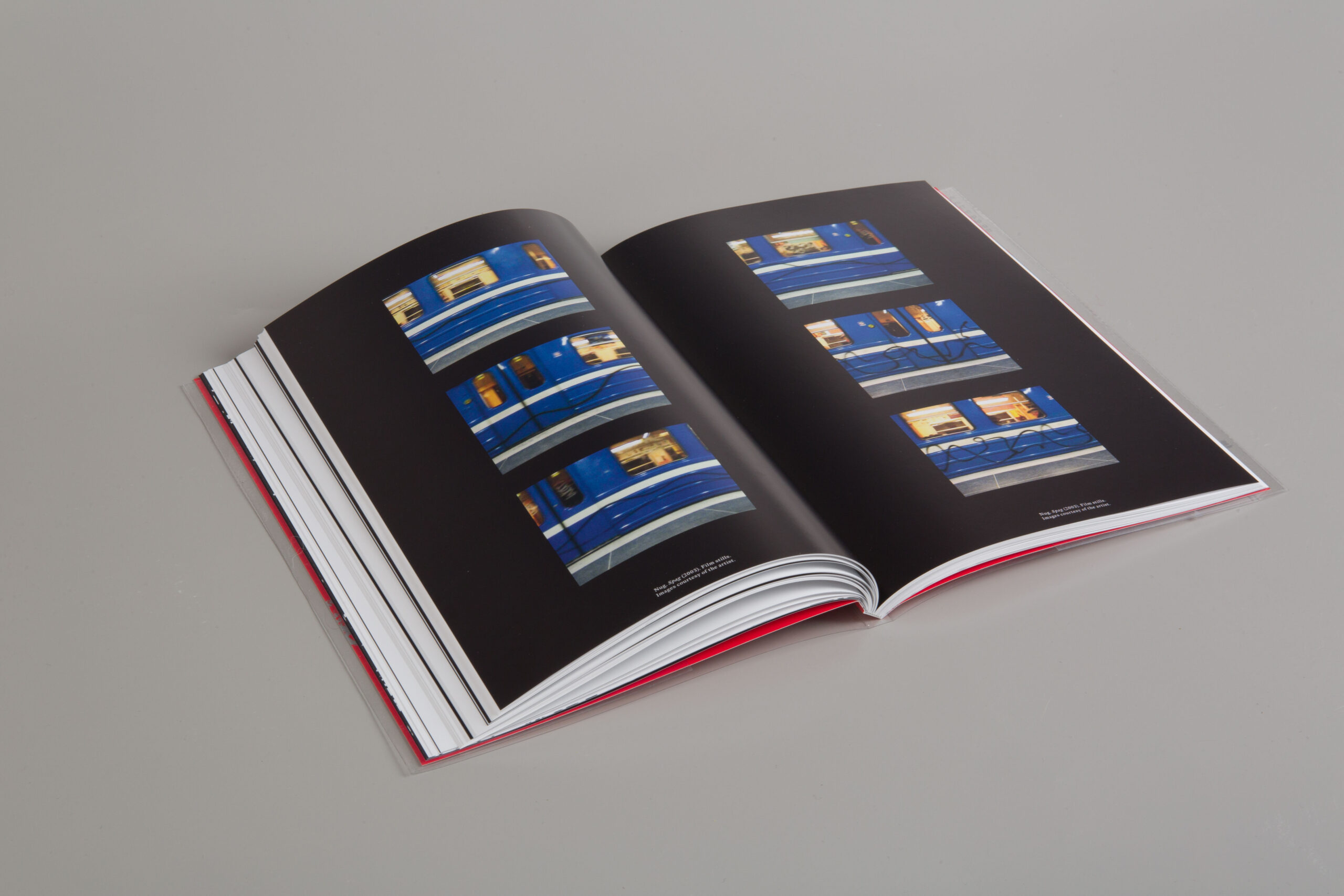

Stephen Burke (SB): Yes, definitely! I’ve been drawn to graffiti since I was young. The way it interacts with the environment, especially when well placed, is something that really appealed to me. Also the mystery of the characters involved is something that’s magic when you’re younger. But I’m also interested in how it could be pushed in different ways, how the ideas of graffiti can be brought into an art context and transformed. I look at this field as a conceptual and material meeting point for these two worlds, which are different in many ways. It’s taken a long time to get to this place artistically, stylistic crossovers from the street into the studio have been common, but it’s a bit more rare to see people bring the feeling with them. That’s why I started the IG account, because I could see it happening more often. I wanted to archive how artists bridge these worlds in experimental ways, practices that bring a new quality.

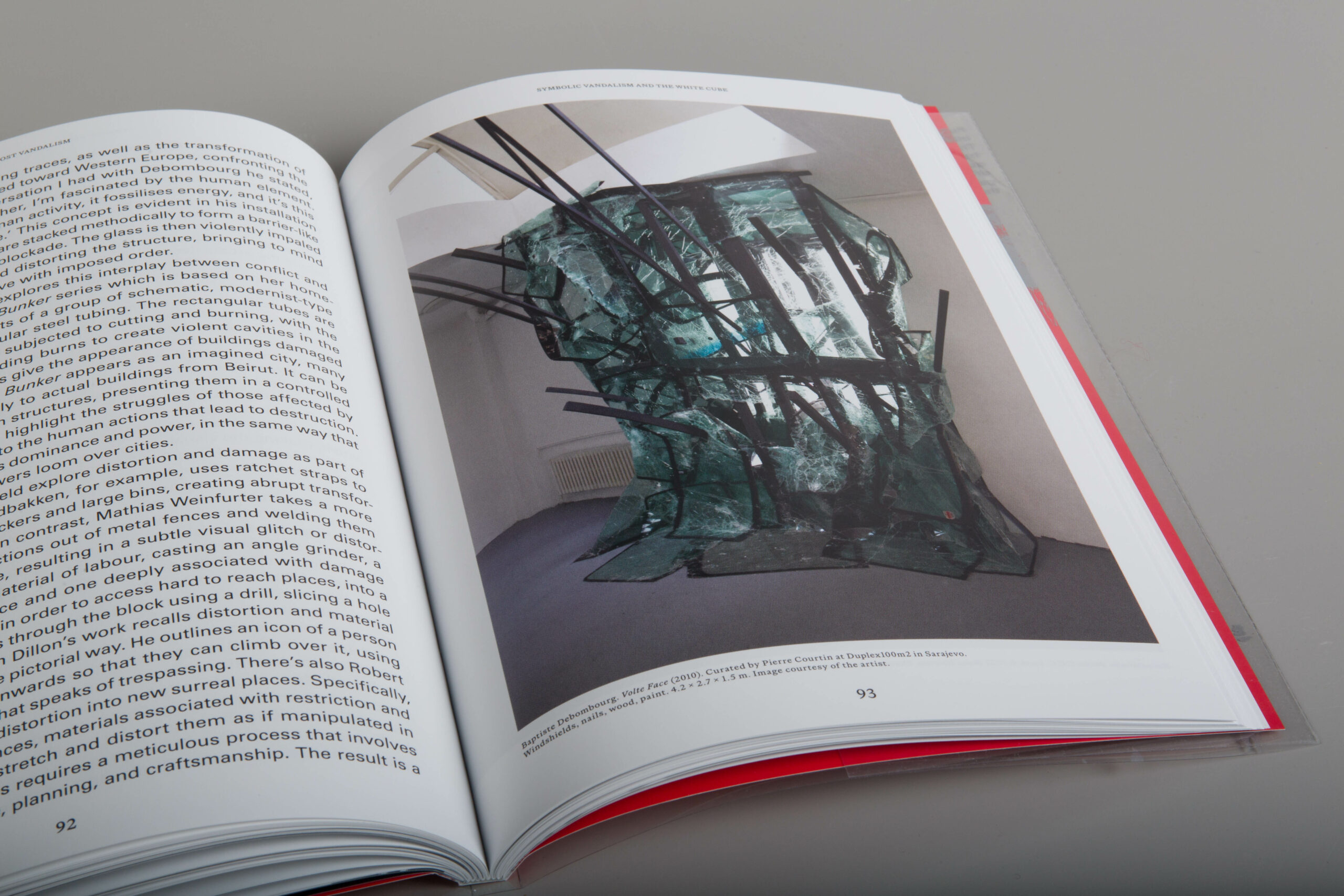

AC: Do you think that Post Vandalism is a retroactive category? In the history of art you can definitely detect this same approach of damage-to-create. To give some examples I think of Fontana piercing canvases, Jimmie Durham stoning a refrigerator or Yves Klein and Alberto Burri burning materials.

SB: Like you mentioned, there’s a long and rich history of damage-to-create approaches that date back into the 20th century and you could probably date some of the earliest examples of what would be considered Post Vandalism back about 15 years ago, so it definitely has predecessors. Lots of today’s artists draw from this history, which is very relevant to them, but the subcultural aspect in this field is a bit different from these historical examples. The artists involved are resourceful and adaptable to public space and that’s learned mostly from subcultural experiences, or being involved in other DIY activities in the street. It’s given them a lot of knowledge that they use when they’re creating. This instinct is very strong in this field.

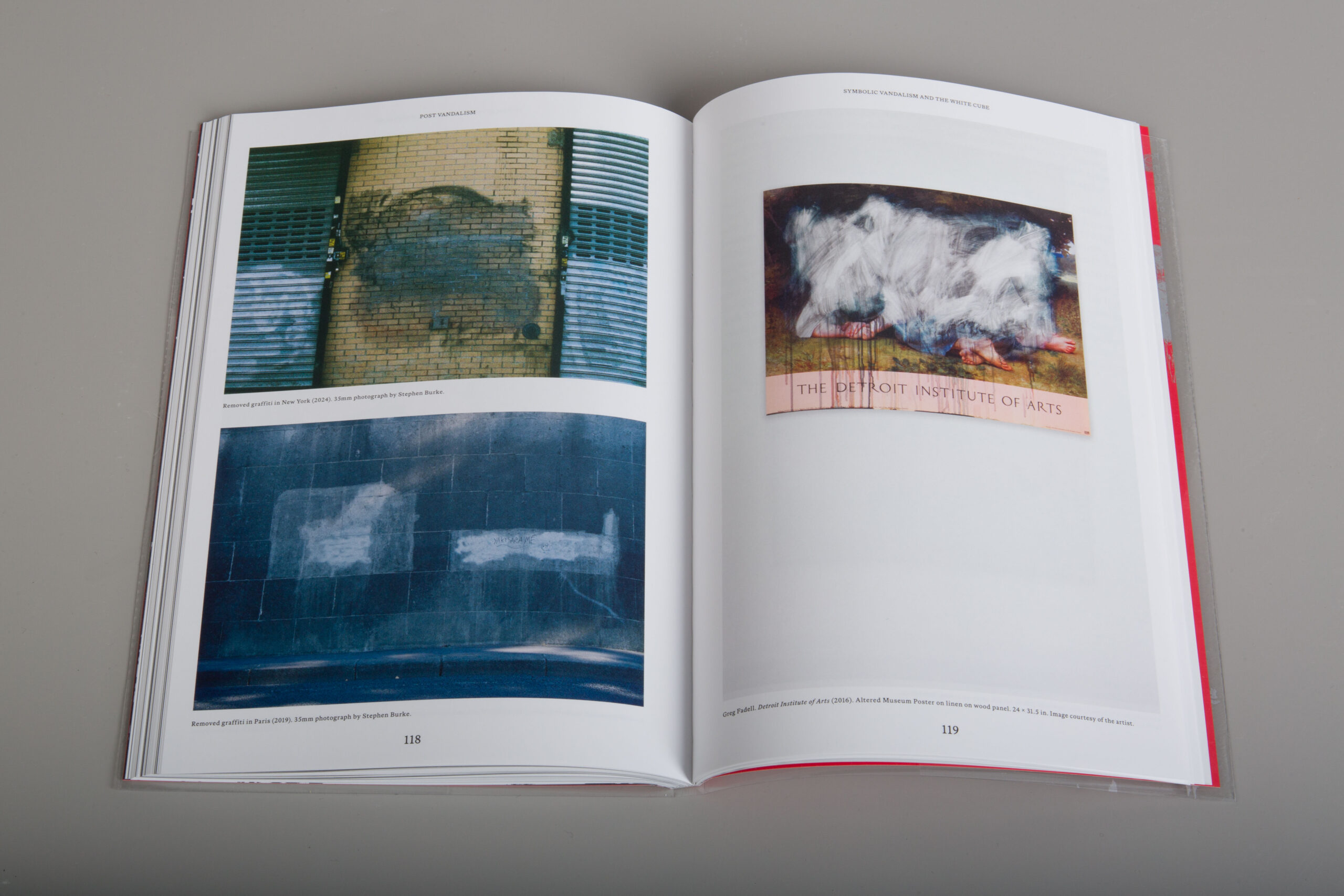

AC: I know that you’ve lived in London. When I was there I could really see the surveillance that you mention in the introduction of the book. CCTVs everywhere, hostile architecture and a lot of buff. Do you think that the British environment influenced your perception and led to the creation of Post Vandalism? Not everywhere is like this: of course my own perception of the world from a small town in the north of Italy was very different, but it also changes from city to city: for example I understood PAL and Saeio better when I visited Paris or the Scandinavian graffiti scene when I visited Stockholm.

SB: That’s a very good question. These qualities definitely shape how we live and what we make art about. For example, I’m from Dublin, and I initially developed an interest in this field when I was growing up there, but I moved to Glasgow to study and that really accelerated my interest. It probably led to the creation of the archive, which I started just after graduating. Glasgow has a very rich soul but it can also be quite harsh. You can feel the ghosts of its industrial past, which make for interesting relics of a bygone era. There’s also plenty of experimental art and music happening, and some nice DIY spaces. It has a particular kind of charm that you could only feel if you spend some time there. You should visit some day!

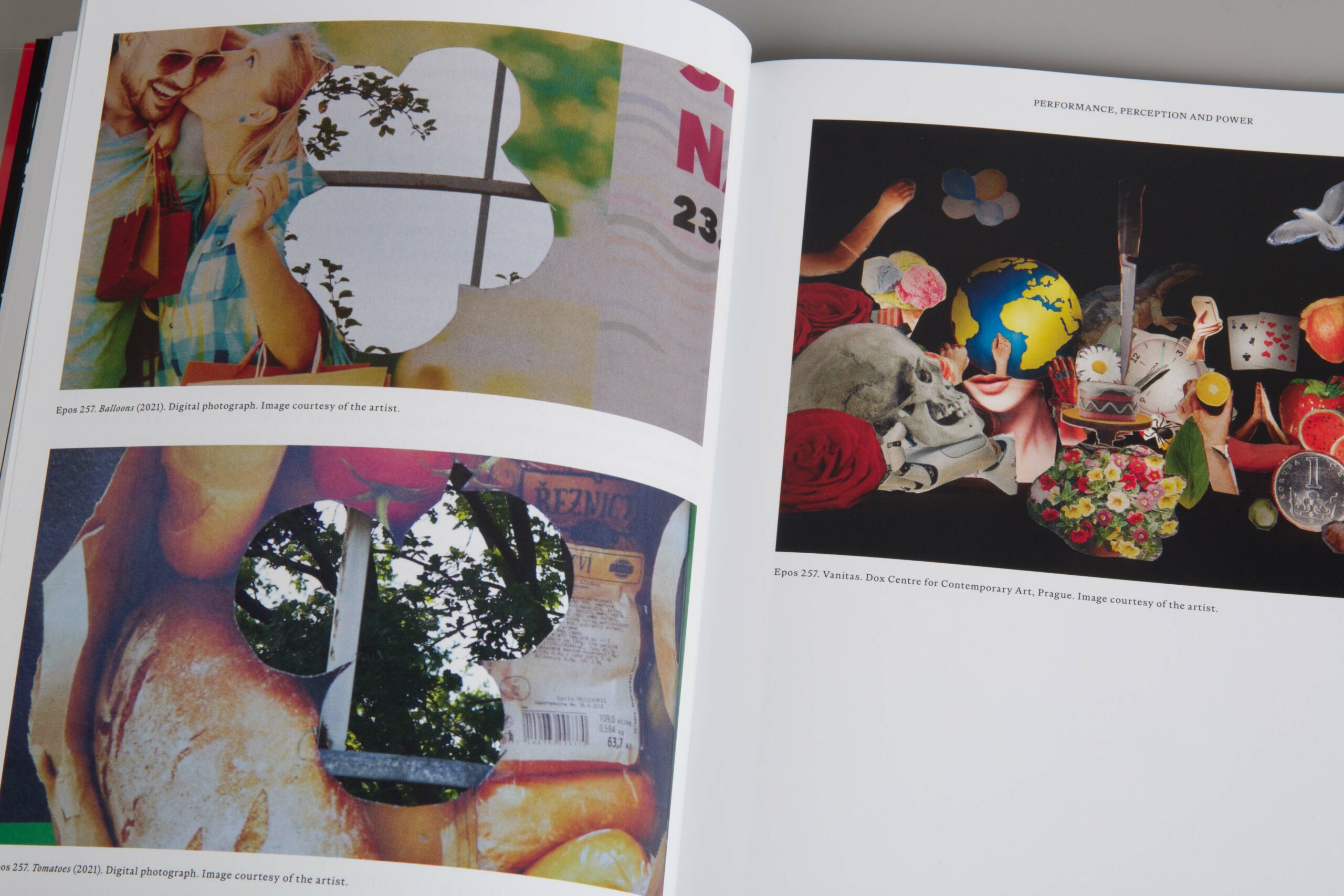

I’ve also lived in Berlin, which of course has a lot of interesting things happening in the street, and last year I did a residency in Prague through the invitation of Epos 257, which was also really inspiring. There’s a great scene there, and like you mentioned about Paris and Stockholm, Prague has its own thing going on that I only really understood through being there.

AC: I have followed the page since the very beginning, I immediately thought that Post Vandalism was a very clear tag that could reunite a certain aesthetic more and more present. I remember that I read a sort of manifesto that you published and that’s where I read for the first time a problematization of gender. Vandalism includes violence and aggressiveness, values normally linked to a machista approach. What is the proportion of men and women doing this kind of work? The graff scene, for example, is well known to be almost only a male environment.

SB: Some of the works in this field may appear aggressive, but they’re usually balanced with a deep care for public space and how we live together. They’re sensitive in how they’re produced, in a way that’s not usually present in typical acts of aggression.

Yes, gender is an issue here. It’s not as male-dominated as graffiti, but it’s still mostly men. That doesn’t mean there aren’t many women creating incredible work though, like Mona Hatoum, Coco Bergholm, Nadia Kaabi-Linke and Katharina Grosse.

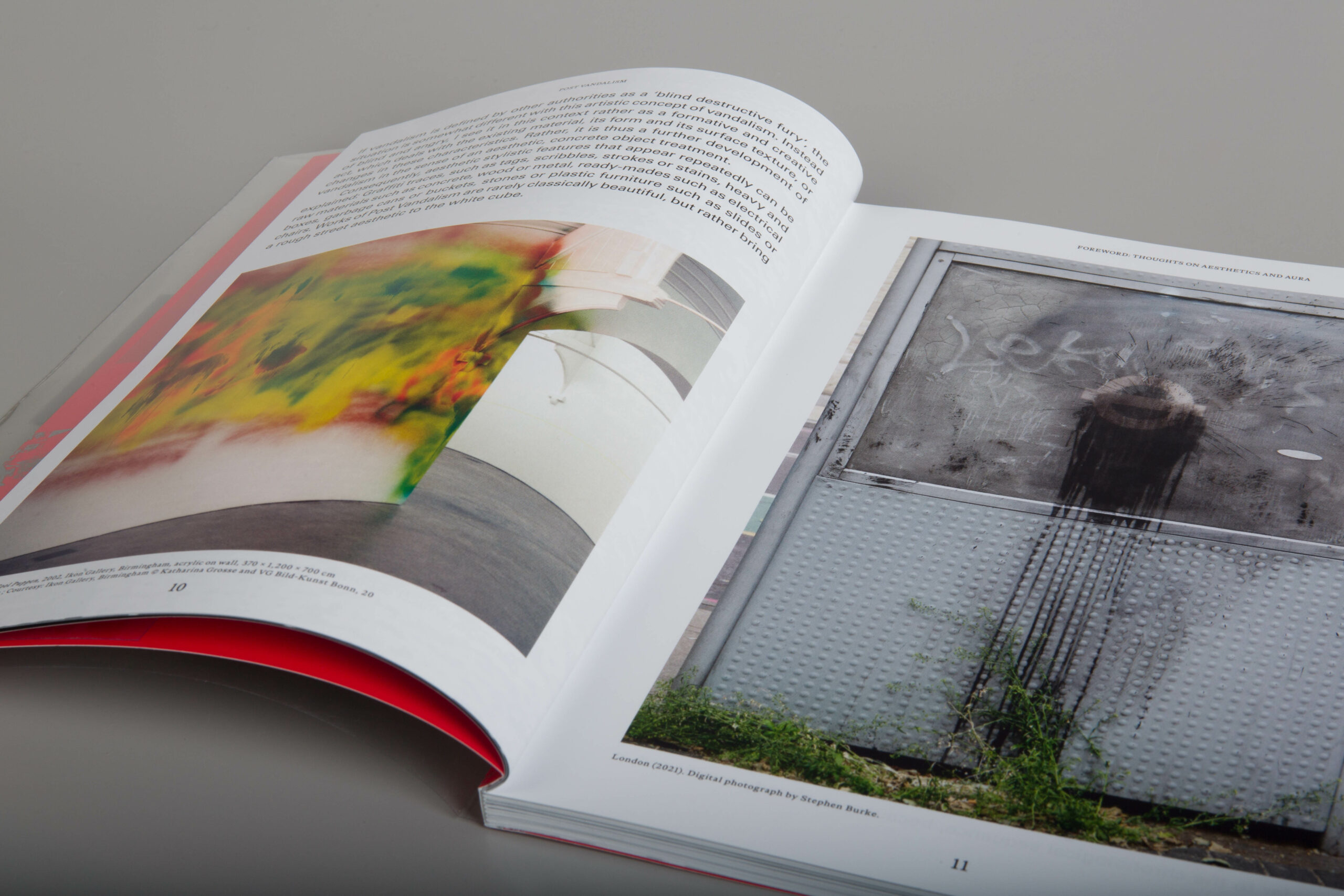

There are also women art writers who have helped shape this field in a really significant way. For example, the intro of the book is written by Larissa Kikol, who has been influential in the recognition of this field. She was responsible for the Kunstforum International edition that was dedicated to Post Vandalism, which introduced this type of work into much wider cultural conversations. She really took the torch and ran with it.

When I first read her writing about Post Vandalism I was amazed, she got it and could put it into words in a way that only someone who really understands it can. It was the first time I had seen Post Vandalism explained so well. There’s also Friederike Hauser, who wrote a short essay in the book, she’s a criminologist and has another interesting perspective on this field. So while things may at the moment be disproportionate in art-making, there’s definitely an established critical element that’s being pushed by women.

AC: What kind of research do you do to keep the page? What led to your research of the artists and the pieces in the book? How complete do you want to be? I ask this because as it is a successful page, you are also a reference. Now that it is hard to create movements in the art field, do you feel any responsibility? Do you think of yourself as a critic?

SB: A lot of the research is done online or through books. Some of it comes from subcultural networks or recommendations from people and often it can come from just meeting people at shows. For example, I was part of the Völklingen Hütte Bienniale in 2024. I found that very inspiring and met lots of new people that are really great artists and ended up being included in the book. It opened up a new community for me.

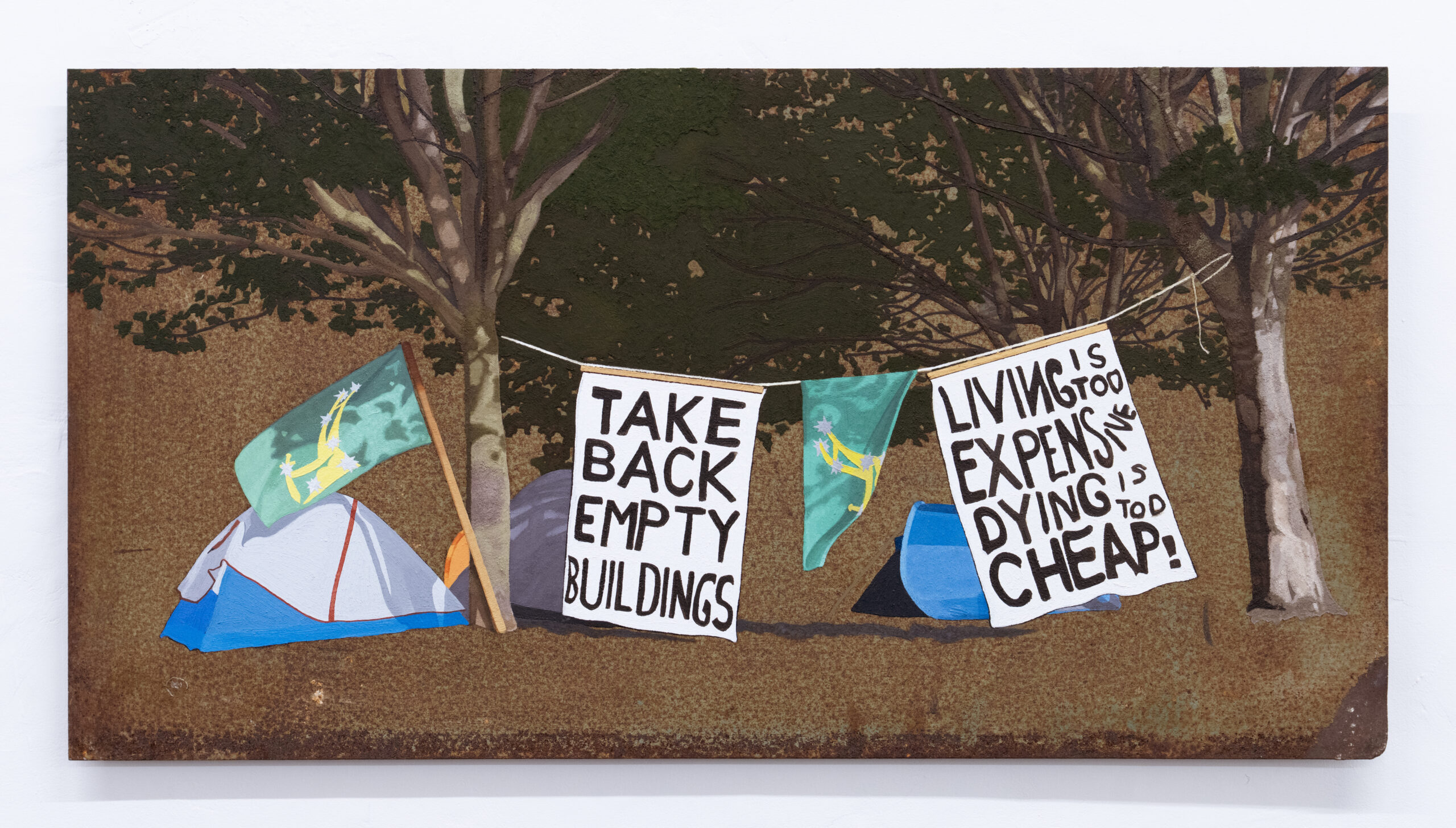

For the pieces chosen in the book, they’re picked because they have a strong feeling, they can place you somewhere else mentally and make you question things. I don’t aim to be exhaustive with the artists I choose, I wouldn’t be able to do that anyway because I’m finding new references and artists all the time! For example, the gallerist Sahil Arora has been sending me lots of artists from India recently and their work is incredible! That’s a whole new area for me that I’m keen to learn about.

As for feeling some responsibility, a lot of the time this type of work isn’t really given the chance to breathe because it can carry the weight of a negative stereotype, that it’s mindless, the usual superficial comments. I know it can be hard for people to see the value in these works sometimes, especially if they’re not connected to this way of working, but these stereotypes are false here! And I think collectively there’s a responsibility to show people that there’s a real human value in this way of working.

I don’t know if I consider myself a critic, but I know what I like! And there are some criteria for artworks that I post online.

The IG account wasn’t started to create a movement either, it was made to archive what was happening. The use of an ‘ism’ was a tongue-in-cheek way to poke fun at an art world that’s mostly overlooked this way of working, with only a few exceptions that were ‘acceptable’. It was a way to reclaim that.

AC: You also made some exhibitions with Post Vandalism, what was your work on those occasions? Which were these occasions?

SB: Yes, there have been shows in Amsterdam, London, Dublin and Rome. I’ve learned a lot from these experiences and from just working with galleries in general. I’ve always tried to balance the role of artist and curator in these shows, which can be hard. I don’t know if I’ll always be able to do that. These days I try to be more selective about who I work with on shows because I’ve had some bad experiences in the past. Looking forward, there’s a couple of showings coming up that I’m very excited about, but I can’t say much more than that.

AC: I feel that in Post Vandalism the threshold between art and vandalism is often blurred. Vandalism in itself could be a sufficient shift from reality, from the established to be considered as art. Heiner Blum, a well-known professor of the Offenbach art academy, once told me that when he was young he put fog in the subway station with some friends « just for fun », not for artistic purposes. But that’s enough in my opinion. What do you think?

SB: It walks a fine line between the two and mostly exists in a kind of grey area, which is where a lot of interesting things happen! The art world can feel a bit stale sometimes and for me this way of working is exciting and offers a different perspective that’s more grounded in reality. Although who knows what it’ll evolve into or whether this kind of work will even continue being present in galleries. Heiner’s fog action is a bit of a metaphor in this sense, we’re walking through unknown terrain right now and we don’t really know what’s coming next, but that’s also part of the fun!