Napal, one of the first graffiti writers to emerge from Rome, is back in Paris with a single painting. Not a retrospective, not a body of work — just one canvas recently sold to a collector. Painted in 1990, it is the first he ever made and possibly one of the first graffiti canvases made by an Italian writer.

At the time, Napal had already spent years painting walls. This canvas did not mark the beginning of his practice, but a shift in how he approached it. For the first time, he attempted to translate graffiti into a different format — one that imposed slowness, permanence, and exposure.

That painting stands at a turning point. The year 1990 concentrates a series of events that would shape everything that followed: travel, illness, chance encounters, moments of confrontation. It is not simply a date in Napal’s chronology, but the moment when his trajectory began to accelerate.

It was also the year of his first trip to Paris.

But the story does not start there.

Le Grand Jeu: Before Europe, before Rome — where does your story with graffiti truly begin?

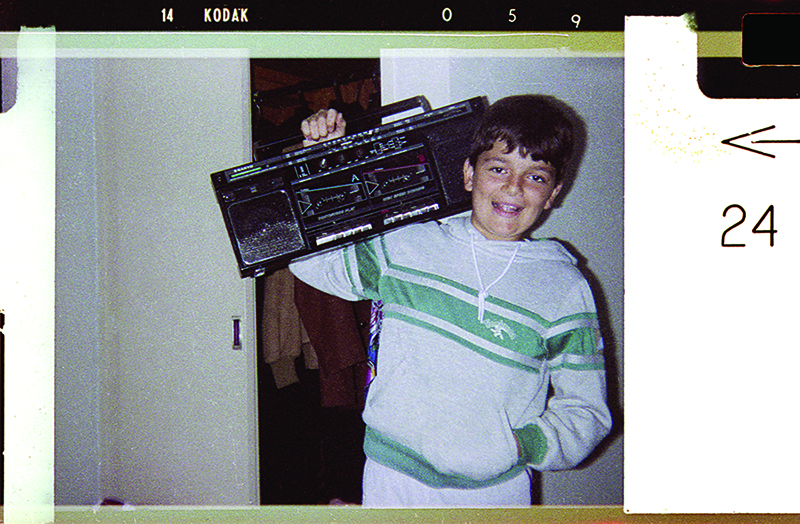

Napal: Australia. 1985. I was ten years old. That’s where my memory becomes sharp. Before that, everything feels blurred. Hip-hop culture existed — breakdance, films like Beat Street — but it was distant. You sensed it, but you weren’t inside it. The first real contact came through conflict.

There was a kid called Defsky. He was fourteen, already a breaker and a writer. Our families owned restaurants near each other. One afternoon he and a friend were circling me on their bikes, bullying me, telling me to “go back to your country.” The 80s weren’t exactly sensitive times. My father saw the scene from the back of the restaurant and shouted at me in Roman dialect: “Throw something.” There was a bolt in a bucket nearby. I threw it. It hit him. He fell off the bike and started crying.

The next day we became inseparable.

Through him I discovered breaking first. It was physical. Immediate. Your body understands before your mind does. Then he took me to see writers painting illegally behind a disco — giant names, beer bottles, spray cans, smoke. I remember the smell of paint. I remember the feeling that this was forbidden.

At that age, seeing something forbidden feels like revelation. That was the lightning strike.

LGJ: You often insist on apprenticeship. Why?

Napal: Because back then you entered graffiti the way you entered a discipline. You learned letters before style. You filled shapes before deforming them. There were steps. Corrections. Humiliations. You earned progression. And there was attitude.

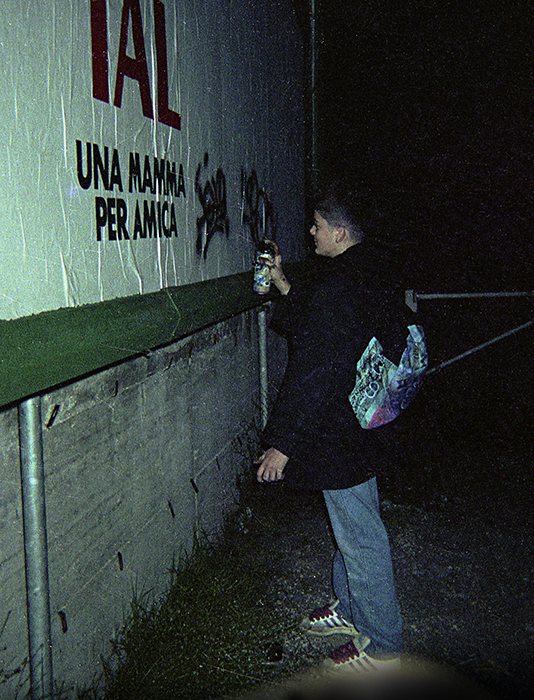

Stealing spray cans was part of it. I was ten years old stealing paint. It sounds absurd now, but painting with stolen cans changes the way you paint. You move faster. You decide quicker. You don’t hesitate.

Years later, when I first came to Paris, writers would leave shops half-naked, running with crates of paint. Today people queue politely and pay with a card. Neither is better. But they are not the same culture. Something was lost. Something else was gained.

LGJ: In 1987 you moved to Rome. What did you find?

Napal: Nothing. Or almost nothing. I arrived thinking, “Graffiti is an Italian word. Rome must be full of graffiti.” But I was disappointed.

I saw GSL with the rabbit — the San Lorenzo group wall writings. Then I started noticing one tag everywhere: CUCS. Every neighbourhood, every wall. I was convinced it was a writer. I kept asking around, trying to find him. Who was this guy dominating the city? It took me a while to realise it wasn’t a writer at all. It was Comando Ultrà Curva Sud — football territory marks.

Even the first time I got arrested, when I was twelve, the police didn’t ask about art. They asked if it was political. Italy was still living in the shadow of the Years of Lead. Graffiti culture hadn’t arrived yet.

When I talked about graffiti as a culture, people looked at me like I was insane. Even my friends didn’t understand why I was so obsessed. I dragged people along for years. They came once, twice — then they disappeared.

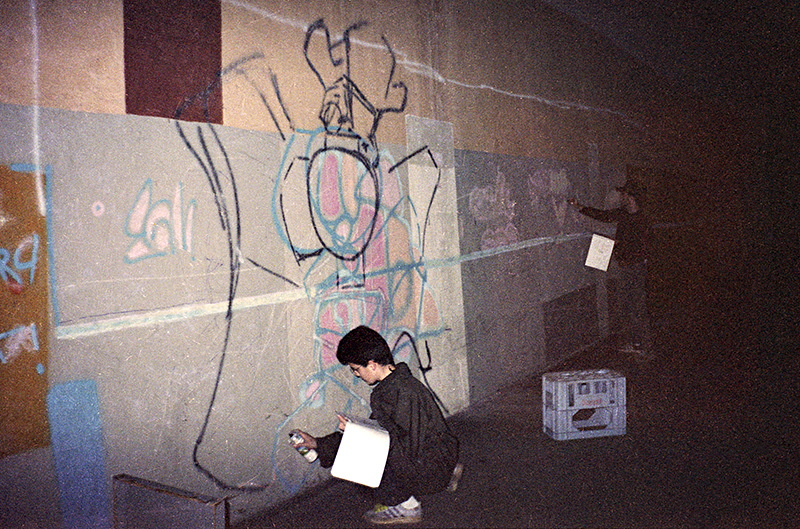

Everything changed when I met Crash Kid. He wasn’t a graffiti writer yet, but he immediately understood the culture. He saw my drawings, my books, and said: this is what we’re here to do. We didn’t convince people by talking. We convinced them by painting.

LGJ: The connection with France seems older than your first trip.

Napal: Yes. The bridge existed before the journey.

In 1990, during the occupation of La Sapienza in Rome, Professor Georges Lapassade arrived with students from Saint-Denis. French MCs, B-boys, writers. They were already rapping in French, living hip-hop on a daily basis. Their level of maturity was obvious.

For us, everything was still fragmented. Crash had the phone number of a guy named Claude. “Call him when you get to Paris,” he told me. Claude was MC Solaar — before the records, before the fame.

LGJ: But Paris wasn’t the first stop.

Napal: No. First came Marseille. The trip itself was improbable. My father was in the hospital and filled out a betting card to pass the time. One number was missing. I added it. It hit. Enough money for a month in France.

In Marseille, I was wandering around the port asking about graffiti. Five guys in a Renault 5 stopped and shouted at me in Italian: “What do you want?” They were IAM — before becoming the legend. They invited me to a hip-hop party in the outskirts.

From Marseille to Lyon — painting in a skatepark, stealing spray cans, moving constantly — and then finally Paris.

LGJ: What did Paris change?

Napal: Everything. I called Claude. He took me to Stalingrad, Saint-Denis, the Ticaret, where I met Boxer. There was no internet. You had to walk to find pieces. I remember seeing the Public Enemy piece by Colt and Mode2. Standing there thinking: this is genius. Not good graffiti. Genius. I had never seen that level — not even in America.

We walked from the métro toward Saint-Denis. I was doing beatbox. He started freestyling in French while we walked. Someone passed by and shouted something. I stopped. He kept going. “Don’t stop,” he told me. “We have to burn.”

Paris recalibrated my expectations. When I returned to Rome, I couldn’t paint the same way anymore.

LGJ: And the canvas?

Napal: The canvas was a consequence. I had seen a documentary where JonOne said: “We paint on canvas to preserve what we do. One day they will understand we were an intelligent movement.” That sentence stayed with me.

There was also my father. He was a painter. My earliest memories are sitting on his knees, smelling oil paint. Even after my arrests, he never shut me down. He told me: “You have something in your hand. Don’t waste it.” Encouragement like that shapes a life.

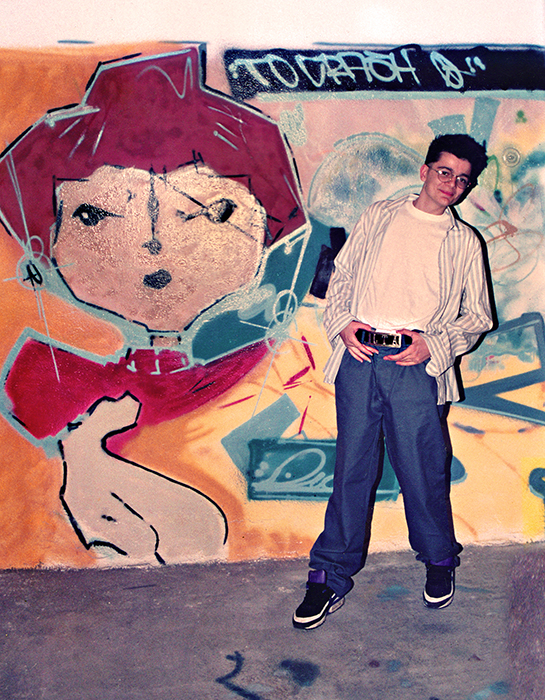

Technically, that first canvas was pure graffiti logic. Homemade colors. Mixing sprays manually. Lowering pressure in the fridge. Double tones. My tag at the time was IoIce — from 1987 to 1991.

After a show in Greece in 1991 everything shifted. It was my first exhibition abroad. I was fifteen. I found myself explaining graffiti to Fine Arts students and professors in Thessaloniki. Until then everything I had done was instinct. No academic training. Just urgency.

I came back with a new name: Napal.

It is not an art of maturity. It’s an art of urgency. Of identity. Of existing immediately.

That’s why it regenerates. Every generation rediscovers it instinctively. Give a kid two spray cans and a wall — something clicks.

I’ve never met anyone who started writing at forty-five. Graffiti belongs to youth. And maybe that’s why it never disappears.

Follow Napal & Explore More

For those who want to dig deeper into Napal’s trajectory and the early European hip-hop network:

-

Follow Napal on Instagram

Ongoing insights, archives, and personal reflections from inside the culture. - Commando Ultrà Curva Sud — Documentary (YouTube)

A raw documentary on Roman ultras culture, offering crucial context around the social and political backdrop of Napal’s generation.

English subtitles can be enabled via YouTube settings. -

Crash Kid’s Books, edited by Napal

One key reference from 2019 documenting Crash Kid’s breaker and writer career, revealing the dedication and the influence that the artist has given to the whole Hip Hop scene and a second book from 2020 focused exclusively on unreleased graffiti images from Massimo “Crash Kid” Colonna’s photographic archive. -

Paris 8 – La fac hip-hop : les Zulus débarquent (ARTE)

An ARTE documentary on the encounter between French students and the Zulu Nation in the late 1980s, thanks to French sociologist Georges Lapassade.