With Iraq Walls, British-Mexican photographer Pablo Allison takes us into rarely documented territories—literally and culturally. Known for his long-term work on migration and borders (The Light of the Beast, Migrantes Valientes, Detained Handbook), Allison now turns his lens to a lesser-known visual phenomenon: the presence of graffiti and tags on the walls of Iraqi cities.

But this is no romanticized journey into the margins. Iraq Walls doesn’t offer easy narratives or sweeping generalizations. Rather, it’s a photographic inquiry into what graffiti might mean in a place shaped by decades of war, foreign occupation, fragmented governance, and yet also full of local agency, visual expression, and urban life.

In this conversation, we explore the intentions behind the book, the specificities of the Iraqi graffiti scene, and how to document without projecting—while also discussing the broader political and aesthetic dimensions of writing on the walls in contested urban spaces.

Christian Omodeo (CO): You’ve previously worked on migration, borders, and the politics of movement. What drew you to Iraq and its walls for this new chapter of your work?

Pablo Allison (PA): Thanks Christian. So the work on migration, specifically in the American continent is an ongoing body of work, set up using different creative paths but mainly photography which I continue to push to deliver a message of humanity and resilience of the most vulnerable people of the world.

In terms of this new book (Iraq Walls), I have been very interested in the Middle East region for a while. Specifically Iraq since the invasion of the USA in March 2003. The impact of the mass mobilization of the US army on that region to eliminate the ‘threat of terrorism’ and to end Saddam Hussein’s leadership following the crashing of two planes into the WTC in New York created radical changes in the world.

That’s mainly why I have started to travel to the Middle East to try and understand the political and cultural intricacies and break away from official stigmas and narratives built by dominant countries in the west.

CO: You’ve photographed a wide range of markings—from tags to messages, symbols, and slogans. What kinds of writings did you come across, and what struck you most about them?

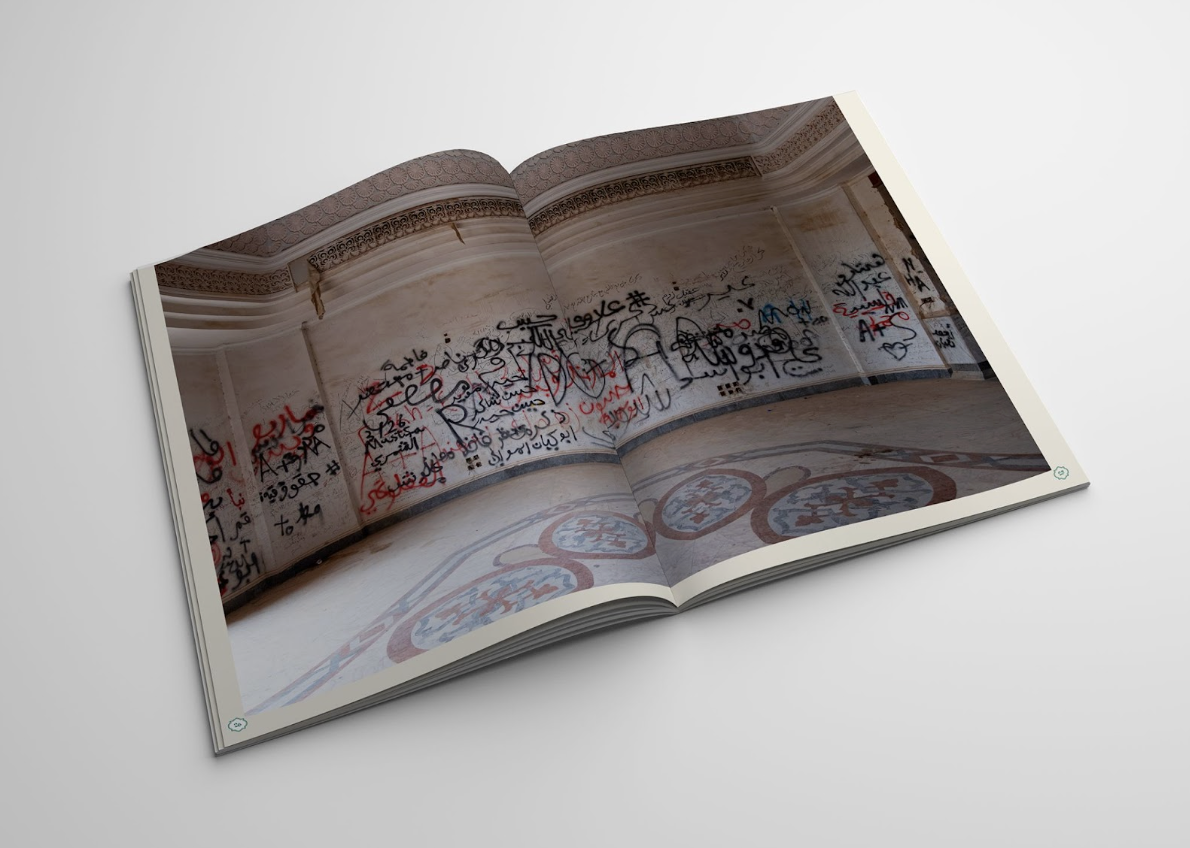

PA: Well, it’s interesting you ask this because when I traveled for the first time to Iraq in 2022 I went with no clear intention other than to observe and understand what was around me. All I had in mind was to visit specific sites that I once viewed on TV at the time of the invasion of the USA and its allied forces. Places such as the green zone, Saddam Hussein’s palaces, monuments such as the Iraqi Martyr Monument, the Swords of Qadisiyah Hands of Victory etc. or the Iraq museum which was looted thanks to the US army etc. were some of the places I visited.

As I was roaming the streets, to my surprise I noticed ‘tags’ on the walls with the beautiful Arabic style but I had no idea what they said. In fact, I really didn’t think I would encounter a graffiti scene there and I actually had no expectations or an initial interest in capturing graffiti there. After travelling around the city for the first two days I asked a friend what the signs actually meant which he kindly translated. I don’t want to give too much away in this interview as I would like the readers of the book to check the story. If you check the book you will find out more about some of the meanings. Aligned with this idea of the documentation of writings on the walls (mainly in Baghdad City), the book’s intention is to use the painted walls as an excuse to capture the landscape and reflect on the country’s past, present and future.

CO: Did you get a sense of what motivates these writings? Are they political, personal, territorial—or something else entirely?

PA: Some of the images relate to the murals produced around the movement of citizens of Iraq, mainly the youth fed up with the repressive government policies, high unemployment, lack of social services, corruption and foreign interference of countries such as Iran and the USA. Such a movement was known as the October revolution or Tishreen protests. The government responded with violence, using live ammunition, tear gas, and other means to disperse protesters. This led to more than 500 murders and many people injured.

Aside from these murals located near the epicenter of the movement (Tahrir Square) in central Baghdad, painted walls using more traditional techniques (brushes and paint) I could observe signs of graffiti based on letters employing spray paint and the roman alphabet. It’s quite hard to find traditional forms of graffiti around the city although you can start to see them due to the influence of social media on the youth.

CO: The notion of a “graffiti scene” may be misleading in some contexts. In Iraq, is there a structured community, or are these acts mostly isolated, anonymous, and spontaneous?

PA: To my knowledge I would dare to say that a graffiti scene does not exist in Iraq (I could be wrong) but I am pretty sure that the marks of what could be considered as graffiti in its traditional form are more like isolated actions conducted by youngsters that emulate what they see on social media and who have an interest in developing their artistic creativity. I personally wouldn’t say that a specific name of a graffiti writer stood out. Trying not to give too much away, the name I saw most up was ‘Crane’, accompanied by a number done in spray paint. It’s possible to see this in all areas of the city, including the surrounding highly secured parts, the palaces that Saddam once owned. On watch towers controlled by the various militias, also known as armed groups backed either by Iran or the Iraqi government (Asaib Ahl al Haq, Kataib Hezbollah, Harakat Hezbollah al Nujaba, Kataib Sayyid al Shuhada, Harakat Ansar Allah al Awfiya, and Kataib Imam Ali).

The amount of security services in the city is shocking. On the one hand you have the state police and private security. Then you have Iraqi soldiers at check points followed by armed forces (Militias) of different political alignment, all spread across the country.

CO: You mentioned collaborating with an Iranian artist/filmmaker who documented graffiti in Tehran and was even imprisoned for it. Can you tell us more about him, and how his experience resonates—or contrasts—with what you encountered in Iraq?

PA: I met Kaywan Karimi in Sweden a few years ago. He is an established and highly accomplished film maker who has carried out many beautiful and interesting films. His work has been showcased at important film festivals such as Cannes, the Centre Pompidou, the Human Rights film festival of Geneva among many more. He was imprisoned in Iran and sentenced to six years in prison and 223 lashes because of the content of a film entitled « Writing on the City » which is a 60-minute documentaru film about graffiti in Tehran. He was released from prison in 2017.

Although Iraq Walls shares a similar idea related to walls and paint, his film analyses Iran’s art on the walls in depth in a few stages. From the years of the revolution in Iran in 1979, to the Iran – Iraq war in the 80’s state propaganda followed by the relationship of street art in the city as well as more traditional techniques of graffiti to disseminate messages of hope and resistance.

The current situation in Iran has made it complicated to actually stay in touch and discuss ways of collaborating but let’s hope that something blossoms in the future and that peace is reestablished.

CO: What was your process for documenting these writings? Did you engage directly with the writers, or did you keep a more observational distance?

PA: Mainly I just roamed the streets in search of the marks on the walls which you can see everywhere but it is much harder to find more traditional graffiti style pieces. Incidentally, I did not manage to find that many political slogans or maybe I simply didn’t open my eyes enough. I also took notes of murals I found near Tahrir Square in central Baghdad as artists would leave their Instagram handle. That way I managed to contact around 9 to 10 artists of which I met 6 and interviewed them. To this day I still keep in touch with some artists.

CO: As an outsider documenting urban interventions in a region with complex histories and sensitivities, how do you position yourself—are you a witness, a translator, an interpreter?

PA: That’s a key question actually. The whole reason I decided to emphasis on the writings on the walls as opposed to documenting a more sensitive social topic in the country was due to the fact that, a) I didn’t have the necessary elements to delve into the photodocumentation of a place rich in history and surrounded by injustices created in a big way by the greed of the West. And, b) I didn’t spend enough time to do more research on the ground. In the end, I didn’t see these two factors as disadvantages as I effectively decided to produce something that indirectly generates a conversation surrounding the recent past, present and future of the country. Utilising the paintings on the walls (call them graffiti if you may) as a detonator of a conversation.

That said, I also felt much more qualified and confident to document the marks on the walls than to talk about a land I am not familiar with. I was very critical about the value and importance of this body of work and I had many conversations with myself and friends about why to produce this book.

Finally, I have spent over 8 years documenting migration from Central America through Mexico and into the USA and I believe that in order to talk about a complex topic it’s important to dedicate a fair amount of time in order to showcase it. One or two journeys are not enough to depict things in an ‘objective’ and accurate way.

CO: Some scholars, such as Charles Tripp, who wrote about The art of resistance in the Middle East, suggest that graffiti in the Middle East functions not only as protest, but also as a form of memory-making and spatial negotiation. Did you see traces of this? Were the walls speaking to the present, the past—or both?

PA: As I previously mentioned, I personally did see that many messages painted in spray paint around the city that generated a political discussion and I travelled quite a lot around the city by foot. I suspected that there was a suppression of such messages from the government perhaps. The closest political paintings on the walls related to the anti ISIS sentiment such as the image below which is a portrait of Iraq riding itself from ISIS.

CO: How would you situate Iraq Walls as a book? Is it a visual essay, an archive, a political document? What kind of afterlife do you hope for?

PA: It’s a contemplative view that I hope invites people to reflect on a place deeply hurt by wars created by the West for dominance and geopolitical reasons. This book intends to showcase the paintings on the walls with the back end intention to meditate on this region and what is happening to its surroundings as I previously mentioned.

What happened in Iraq is not an isolated case. That is, the excuse to stir a population and convince them about the need to attack ‘the enemy’ of the world. We are seeing this unfold once again with Iran although we now have more elements to inform ourselves like the power of social media to understand more about what is really going on, away from the official state propaganda channels such as CNN, FOX, BBC etc.

Finally, I would say that I guess it’s the first book that sheds light on the relationship between Iraq and graffiti. Though Iraq might not be a relevant country to graffiti, I think that its history makes graffiti relevant and interesting there.

CO: You mentioned future plans—possibly involving other cities, or collaborations. What’s next for you?

PA: The idea is to extend this body of work to other key areas of the region to create a sequel to this book. The situation there however is extremely volatile so lets see how things progress.

At the same time I continue to work on the documentation of migrants heading to the USA so that will keep me busy for the foreseeable future.