Le Grand Jeu did not start as a bookshop. It started, quite simply, with books.

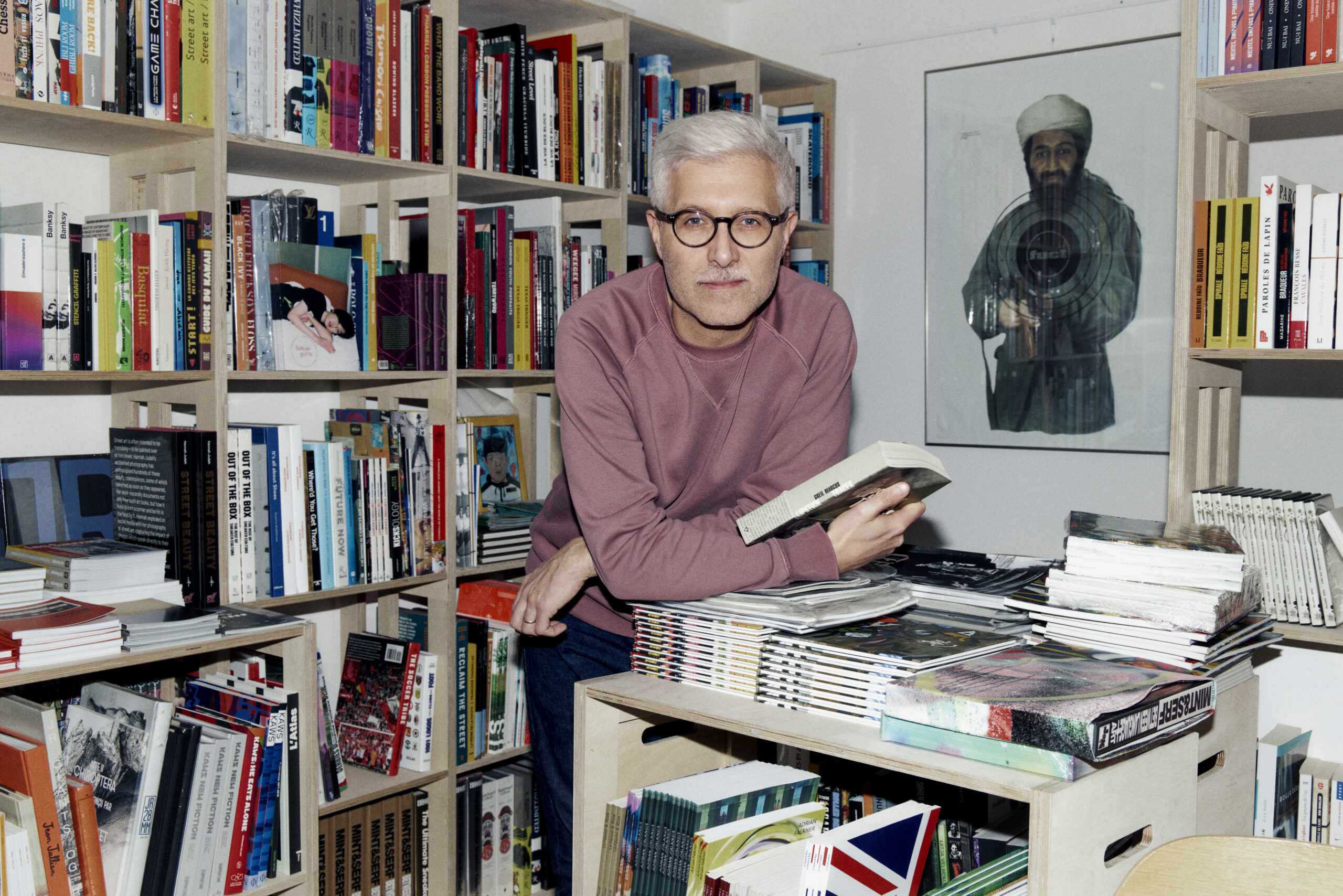

At first, in the 2000s, I was buying them for myself. Catalogues, artist books, obscure publications, out-of-print titles—anything that could feed a growing documentary archive around graffiti, lettering, underground graphics, and youth cultures. As the collection grew, I quickly realized that buying books individually was neither sustainable nor efficient. So I began acquiring entire collections, often in bulk. It was the only way to access certain titles, and to do so at a reasonable cost.

That was when the first duplicates appeared. Then triplicates. And slowly, a side effect emerged: I had more books than I could ever keep.

Rather than seeing this as a problem, I treated it as an opportunity. Selling those duplicates became a way to finance further research and acquisitions. The very first iteration of Le Grand Jeu in 2014—then only an online shop—was essentially a second-hand and rare book selection, built from these surplus copies. It was not yet a “curated bookstore” in the traditional sense, but rather an extension of a personal archive in motion.

By word of mouth, people began to contact me directly. Some knew I was buying collections. Others had libraries they were ready to part with. Around the same time, artists and editors started reaching out as well: “I’ve just published a zine,” or “I’m working on a small book—would you be interested in carrying a few copies?”

Le Grand Jeu was still fully online at that point, with no physical space, but it had already become a node where books circulated.

A telling moment came in 2016, when I took part in the Unlock Book Fair in Barcelona. Almost everyone else there was an independent publisher presenting new releases. I arrived with something slightly out of place: a carefully selected set of rare and out-of-print books—my duplicates and triplicates—assembled for graffiti writers, letter enthusiasts, and visual researchers. In retrospect, that fair felt like the first time Le Grand Jeu publicly assumed the role of a book dealer, even if I still didn’t think of myself as a bookseller.

As the project grew, so did its visibility. I began doing pop-ups at fairs and events—Urban Art Fair, White Street Market in Milan, Moniker Art Fair in London in 2018, and later in New York—and I still do so today, occasionally, in contexts such as the Paris Surf & Skateboard Film Festival or the Art & Place Conference. At the same time, the editorial and curatorial side of my work was expanding, and it became clear that I needed a dedicated space: not a shop yet, but a base.

In late 2017, I rented the space at 15 Passage de Ménilmontant, where Le Grand Jeu is still located today. The intention was pragmatic. I needed offices for my team, storage for documentation, and a logistical hub to manage online sales and pop-ups. The idea of opening a public bookshop came later, almost as a consequence of necessity.

Around that period, something else shifted. While rare books had played a crucial role in the early years, I increasingly felt their limits. Rare copies circulate slowly. Sometimes it takes years to find a single example. And more importantly, access is restricted—often reserved for those who can afford high prices. That was not what motivated me.

What mattered more was access to information. I wanted books to circulate, to be read, handled, shared. I wanted anyone interested in these cultures—not just a handful of collectors—to be able to access their history and visual language. That conviction naturally pushed Le Grand Jeu toward new publications, even if that meant relegating rare books to a secondary, sometimes discreet, position.

By 2018–2019, the dynamic was clear. People started coming by the space. The first room gradually turned into a showroom, displaying a selection of titles available through the online shop. Events and pop-ups multiplied, and soon other venues reached out with proposals to host permanent bookshops. Two in particular marked that moment: Fluctuart in Paris, which opened in summer 2019, and Hangar 107 in Rouen.

Then came COVID.

The timing could not have been worse. Significant investments had been made to develop the bookshop side of Le Grand Jeu, just as the figures from previous years did not yet reflect the growth underway. The pandemic disrupted everything. But it also imposed a pause—one that proved useful.

That forced break made something clear: managing multiple external points of sale was draining energy from the core project. While those collaborations made sense, they also diluted focus. What I truly wanted was not to multiply locations, but to build one strong, coherent reference space—a place capable of giving visibility and legitimacy to the underground cultures I had been working with for years.

Post-COVID, a new balance emerged. Rather than directly managing satellite bookshops, Le Grand Jeu repositioned itself as an activator—supporting and curating book selections within institutions or cultural spaces, while refocusing its efforts on Ménilmontant. The aim became explicit: to turn Le Grand Jeu into a reference bookshop, at least at a European scale, for publications related to underground and youth cultures.

From 2021 to 2025, the transformation accelerated. The bookshop progressively became the heart of the project. The spaces were fully renovated, documentation reorganized, and the selection expanded significantly. The number of titles grew, events became more frequent, and a community started to take shape—readers, artists, publishers, researchers, and collectors crossing paths in the same place.

These years also coincided with the completion of a long curatorial research cycle around the relationship between institutions and underground cultures, particularly in graffiti and street art. The bookshop benefited directly from that work: not as a commercial outlet, but as an extension of an ongoing inquiry.

Le Grand Jeu was never built by a trained bookseller, manager, or entrepreneur. Everything was learned on the ground—often through mistakes. But those errors were formative. They helped define not only how to run an independent bookshop, but why it should exist, and what it should contribute to the broader ecosystem of publishing.

Today, as the project looks ahead, the questions are once again shifting. How can physical space evolve? And how can a digital ecosystem be developed so that the work done daily at the bookshop can reach beyond Paris?

The answers are still unfolding. But the principle remains unchanged: books as tools, circulation as a method, and access as a political choice.

Part of an ongoing series

This article is part of a series reflecting on how Le Grand Jeu took shape through books, archives, and exhibitions.

– 1. Too Visible, Poorly Told

– 2. Books Before the Bookshop

Filed under: The Bookshop