My relationship with books did not begin as a collecting project. It began while preparing my PhD, spending my days between the Jacques Doucet Library and the Bibliothèque nationale de France. I could find every book I needed for my research—except those dealing with urban art.

In the early 2000s, it quickly became clear that public libraries were ill-equipped to support sustained research on these practices. At the same time, vast bodies of knowledge existed elsewhere—scattered across private collections, studios, and informal networks. This gap between available knowledge and institutional access is where my work with books truly started.

Collecting as Research, Not Accumulation

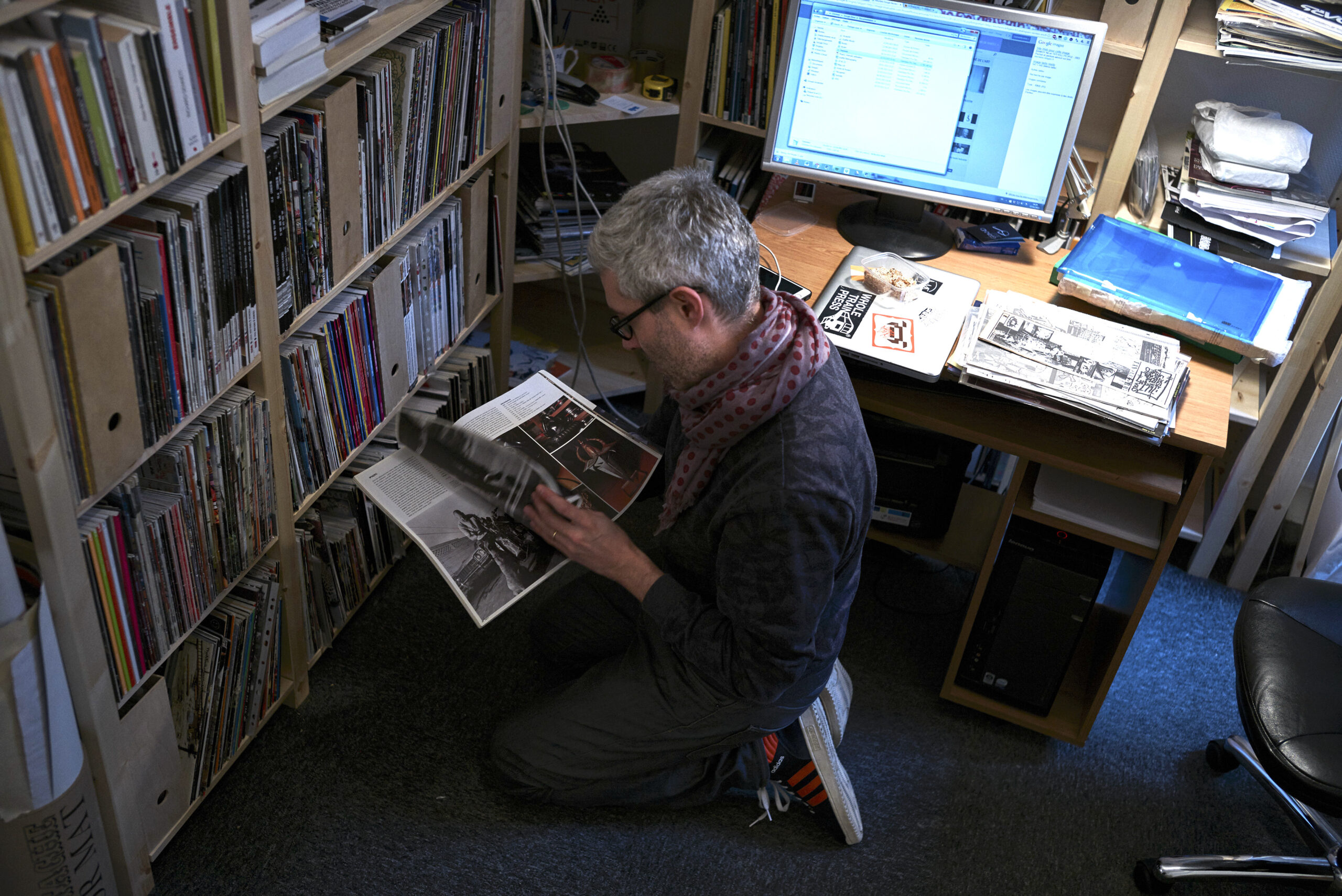

Because I have always been deeply attached to books, my first instinct was to start acquiring them—but not in the traditional sense. I was not trying to build a pristine or prestigious library. What mattered was access to information, not the fetishization of objects.

With a limited acquisition budget, my choices were guided less by condition than by accessibility. I constantly had to arbitrate between editions, availability, price, and content. Some books were worn, annotated, incomplete—but they were within reach, and they allowed me to read, compare, and understand. What I was building was not a collection meant to be admired, but a working tool: a way to map what had already been written, published, and circulated about these practices.

Today, that relationship has evolved. While access and content remain central, I now pay close attention to the physical condition of the books I acquire—not out of fetishism, but because preservation has become part of the responsibility that comes with building, transmitting, and sharing knowledge.

Crossboarding: Turning Books into a Subject

After nearly a decade of accumulating and studying this material, the work took a first public form in 2014 with Crossboarding. An Italian Paper History of Graffiti and Street Art , developed with LO/A (Library of Arts). Conceived as a book about books, the project used Italy as a case study, tracing a continuous narrative from political wall writings of the 1960s to street art in the 2000s, supported by a strong publishing landscape.

The publication brought together around one hundred books, complemented by an extended bibliography and an introductory essay proposing an historiographical reading of urban art—focusing not only on what was produced, but on how these practices were seen and documented over time.

From Bibliography to Public Display

Crossboarding led to an exhibition in Paris, then to a second selection of books and fanzines presented in Venice as part of Bridges of Graffiti, curated by Giorgio De Mitri & Mode 2. Displayed in custom-designed libraries by Boris “Delta” Tellegen, the publications took on a new status.

For the first time, I heard contemporary art audiences express genuine surprise at the sheer quantity of printed material devoted to graffiti—as if the presence of paper alone were enough to confer cultural legitimacy on a practice long considered marginal. Books were no longer just sources; they became exhibition material in their own right.

Berlin and the Question of Access

In 2017, this trajectory led me to Berlin, where I was invited by Martha Cooper, Yasha Young, and Urban Nation to contribute to the creation of the Martha Cooper Library. Its initial core was formed by Martha Cooper’s personal collection, donated to the museum, and enriched by a selection of books and fanzines I sourced to expand and contextualize the archive. Conceived as a public resource, the library aimed to make these materials accessible beyond a purely institutional framework.

The experience reinforced a persistent issue: despite growing institutional interest, access to reliable sources remained fragmented. Books, fanzines, and printed ephemera were still rarely treated as legitimate heritage within public collections.

When Books Become Data

My years at the INHA (Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art) between 2006 and 2012 had already familiarized me with the tools of the digital humanities. It became clear that my work on books required a similar infrastructure. What began as a simple spreadsheet evolved into databases designed to catalogue not only the books I owned, but also those I encountered, referenced, or could not access.

Working on fanzines made the problem even clearer. Basic data—dates, publishers, print runs, variants—was often missing or inconsistent, before it became evident that the sheer volume and dispersion of these publications made them incompatible with traditional public collection models.

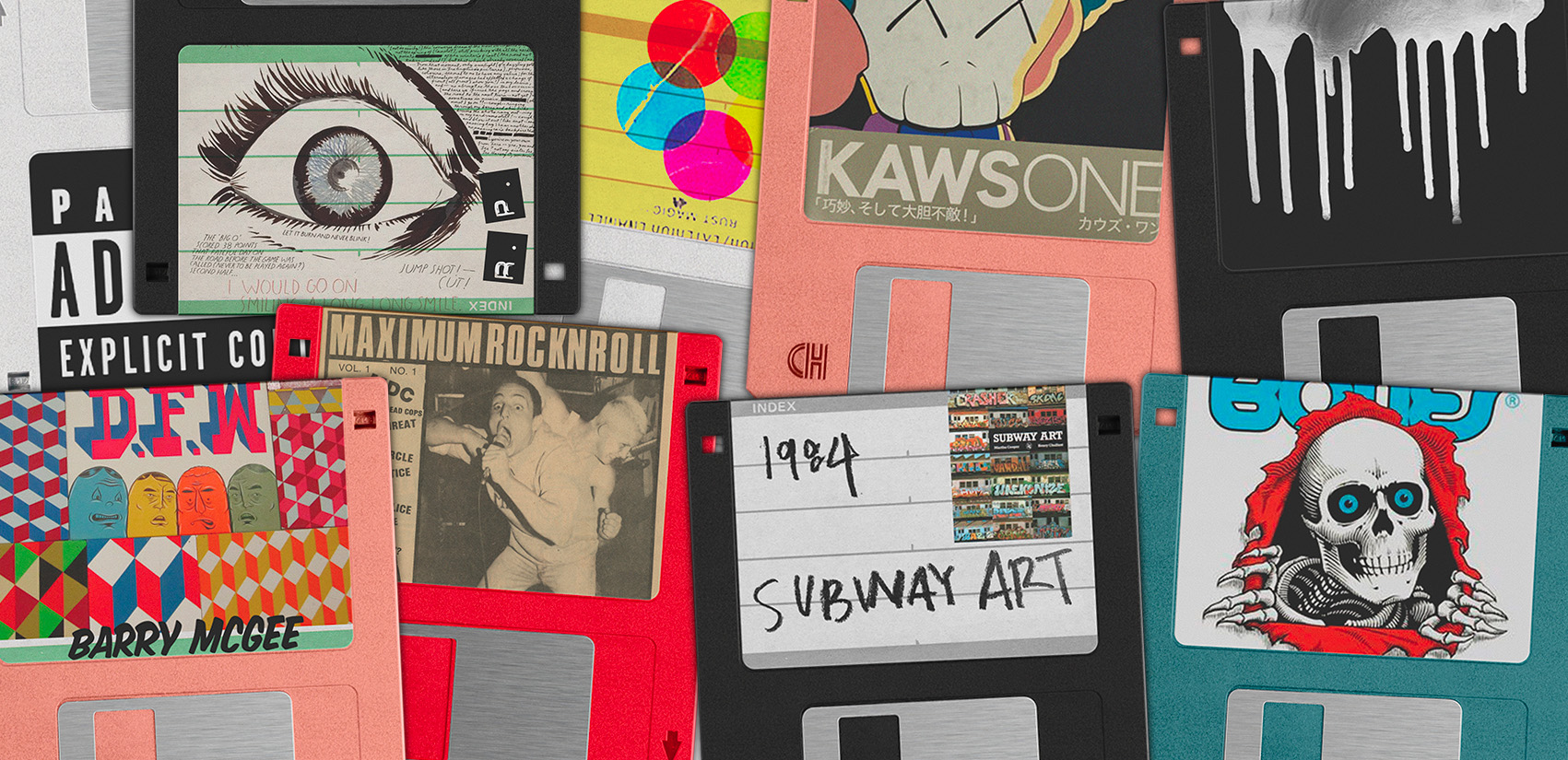

From Grintz to Paperware

In 2017, I launched a first online database called Grintz. Despite funding difficulties and technical constraints, the project continued to evolve and eventually became Paperware—a name inspired by abandonware, a term used to describe obsolete or unsupported software that survives through informal, community-driven circulation. Here, Paperware refers to printed material that has fallen outside institutional or commercial circuits, yet continues to circulate through alternative networks.

Today, Paperware extends far beyond graffiti and street art, encompassing fanzines and underground publications related to countercultures, BMX, ultras, and other poorly documented scenes. The logic remains the same: before acquiring, selling, or exhibiting books, it is essential to understand what exists, in which versions, and in which contexts. A first alpha version of the platform is scheduled to go online in early 2026.

When the Books Leave the Shelves

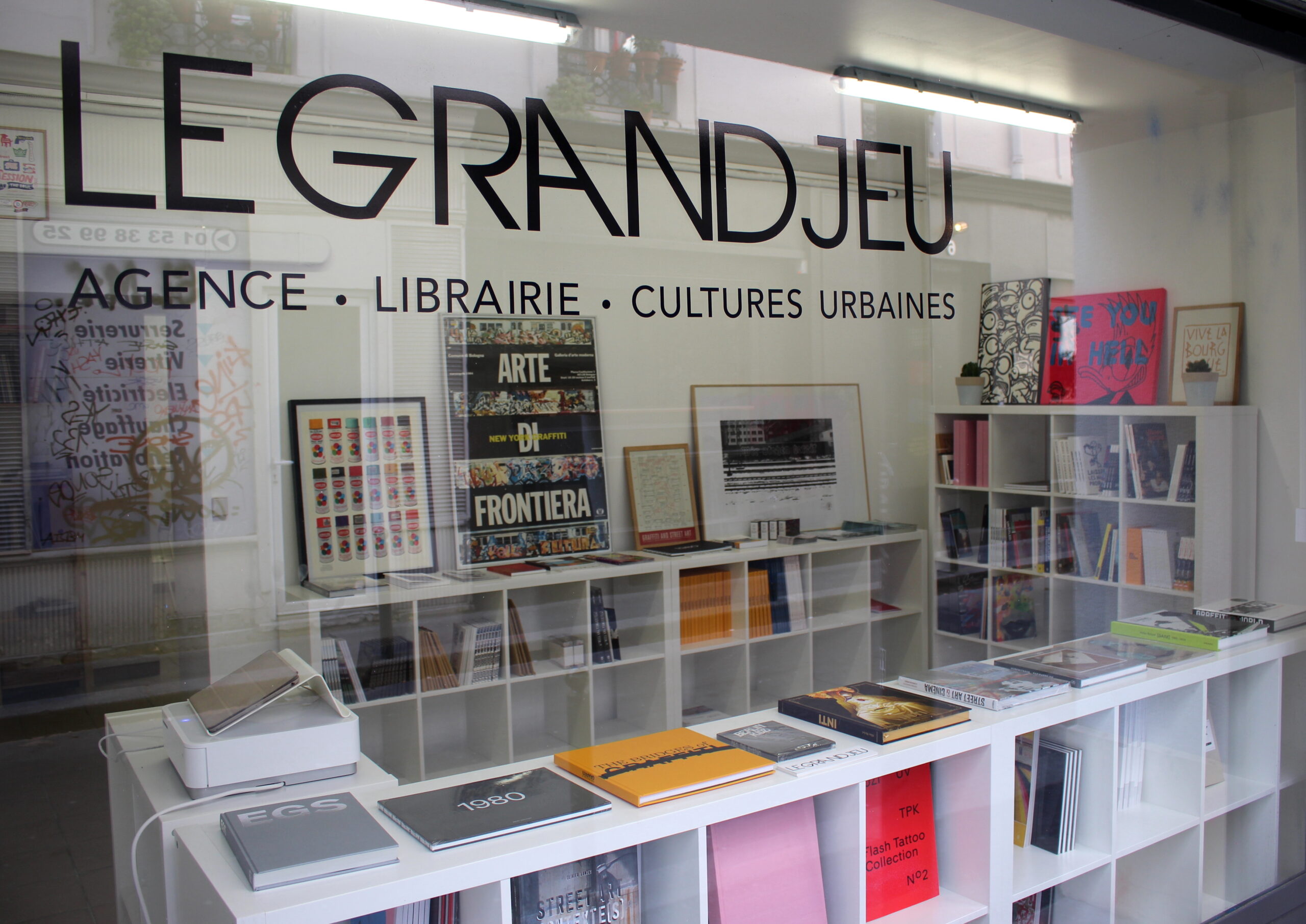

Over time, my personal relationship with books changed. Moves, lack of space, and eventually transforming my office into a bookshop meant that much of my collection ended up in boxes. I often joke that the bookseller eventually killed the book collector. In reality, the shift was less a renunciation than a displacement—from private accumulation to shared circulation.

Some books were sold, partly to finance the development of Le Grand Jeu, partly because certain lines of research felt complete. Accumulation was never the goal; circulation and use mattered more.

Returning to Books as Exhibitions

Recently, this approach found a new expression. Invited by René Kaestner, I curated a selection of books and archives for the exhibition Hallenkunst in Chemnitz, integrated into a large timeline tracing the history of New York and European graffiti. The project also carried a personal echo: it was the first time I met Luca, who had sold me, fifteen years earlier, my copy of Graffiti a New York by Andrea Nelli—one of the books that has mattered most to me.

One of the Pillars of Le Grand Jeu

Books were never just objects in this process. They were tools, infrastructures, and points of entry—ways to slow narratives down and make them transmissible.

Today, this work forms one of the three main strands of Le Grand Jeu, alongside exhibitions and editorial projects. Through Paperware, the Journal, and the bookshop itself, this research continues to unfold as a shared, evolving foundation.

Part of an ongoing series

This article is part of a series reflecting on how Le Grand Jeu took shape through books, archives, and exhibitions.

– 1. Too Visible, Poorly Told

– 3. From Archives to Shelves

Filed under: Paper Trails