« Mais les vrais voyageurs sont ceux-là qui partent

Pour partir ; coeurs légers. »

Charles Baudelaire

When was the last time you used a paper map in a city you didn’t know? You probably can’t remember—and you’re not alone. With smartphones in every pocket, physical tools like maps and guidebooks have been quietly replaced by sleek, digital alternatives. Why carry a printed map when you’ve got Google Maps? Why flip through a guidebook when TripAdvisor or TikTok can tell you what’s “worth it” in five seconds?

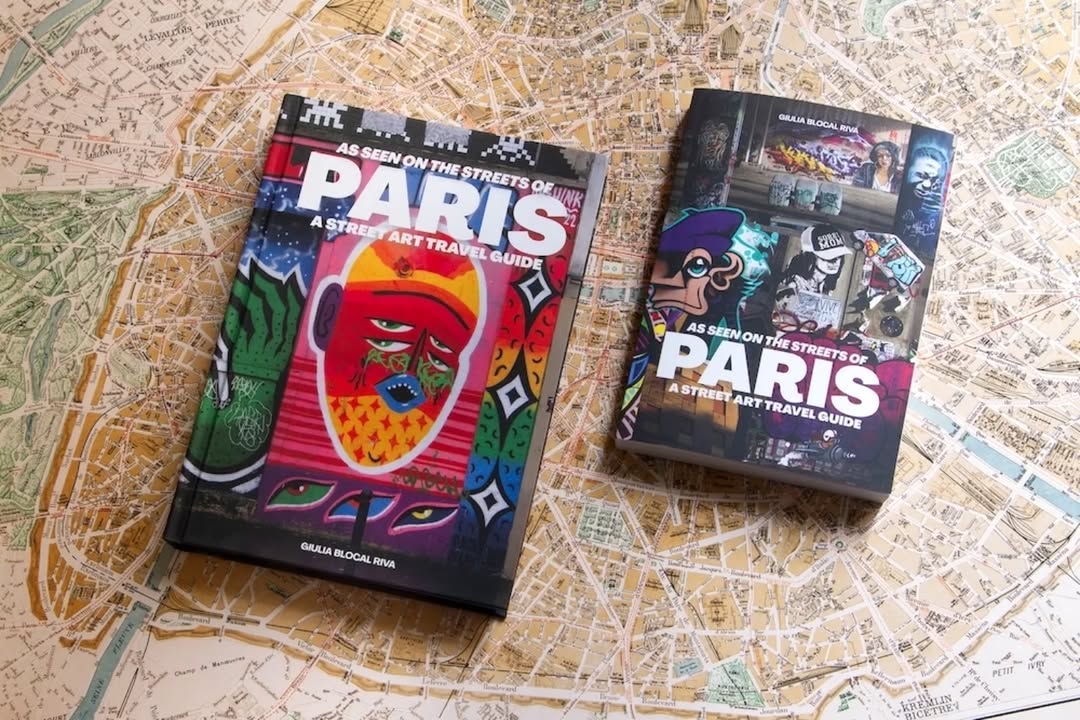

These were exactly the questions we found ourselves asking in late April, as we welcomed Giulia BLocal Riva to the bookstore for the launch of As Seen in the Streets of Paris—a guide we wholeheartedly recommend to anyone curious about exploring the city’s walls through the eyes of one of Europe’s sharpest street art observers.

Now, we know what you might be thinking: in 2025, a bookstore defending printed travel guides might sound like a nostalgic, anti-tech throwback. But that’s not the case—not from a place that literally has a Coding section on its shelves. This isn’t about rejecting the digital world. Quite the opposite: it’s about pausing to consider how deeply it shapes our habits—including the way we travel, and how we inhabit public space. When everything is optimized for speed and convenience, we risk losing the slower, more personal, more human encounters that make travel meaningful in the first place.

Travel by Feed: How Platforms Shape Where We Go

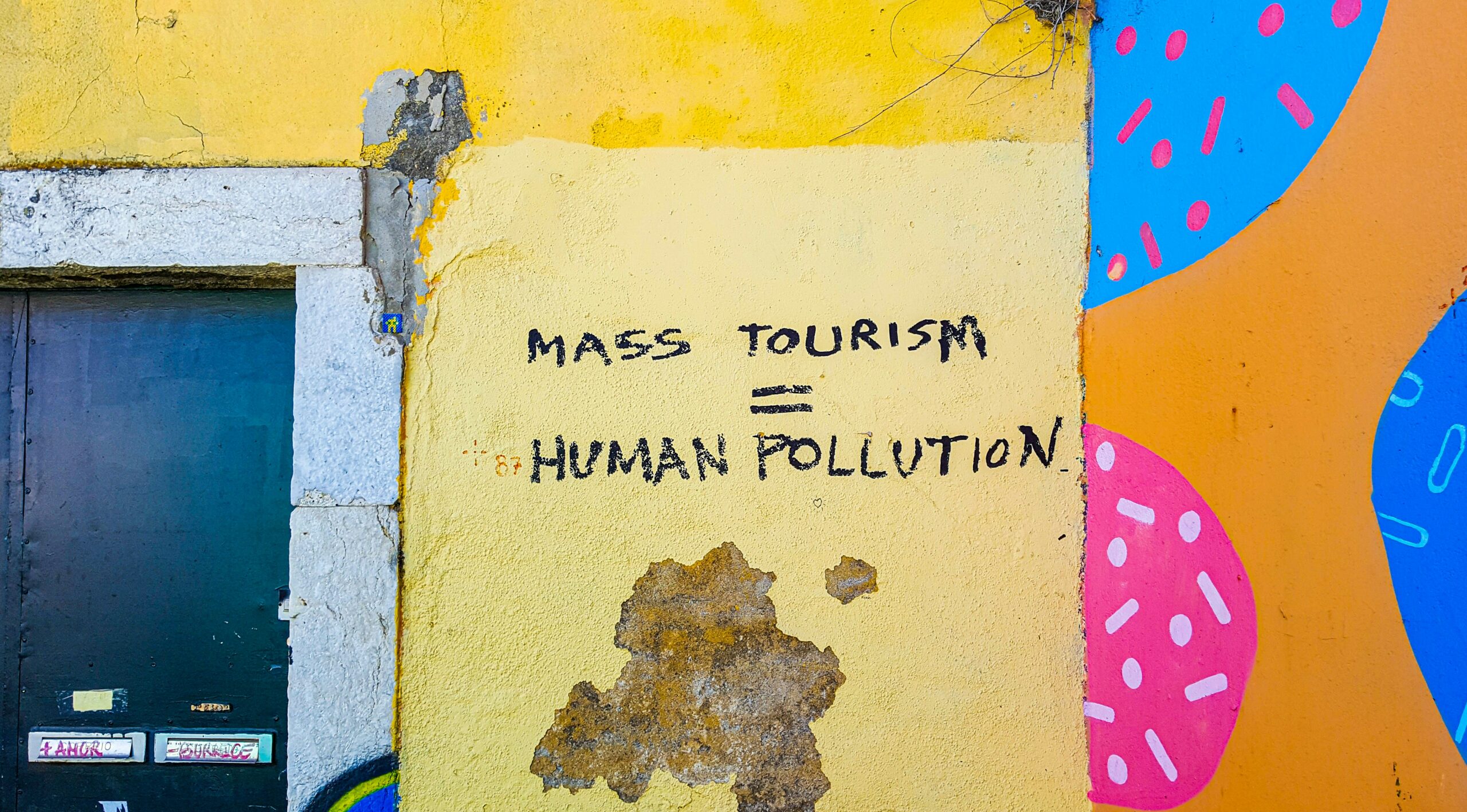

Easy access to information can improve how we travel—but it comes at a cost. Cities across the world are increasingly overwhelmed by tourists who swarm the same cafés, snap the same photos, and line up at the same landmarks.

Overtourism is no longer just a buzzword. It’s the visible outcome of algorithm-driven behavior. More and more people are willing to queue for hours for a trendy restaurant, a must-see exhibition, or even to pay extra for places that were once free and open to all. Think of the Trevi Fountain in Rome—or any iconic site quietly turning into a pay-per-view attraction.

We like to think we’re planning our own journeys. In reality, we often orbit the same hotspots, drawn less by personal interest than by what’s been validated—liked, tagged, and filtered—by others. We’re not choosing what we love; we’re loving what we’re told to choose.

In Filterworld: How Algorithms Flattened Culture, journalist Kyle Chayka explores what happens when we let trends do the decision-making:

« Something was missing: I wasn’t being surprised by the unknown during the trip, I was just reaffirming the superiority of my taste by seeing it reflected in a new place. Maybe that’s why it felt so empty. »

When we rely solely on platforms to shape our travels, we miss out on what only human curation can offer: a sense of wonder, unpredictability, and personality. Real exploration is messy, subjective, and full of surprises—and that’s exactly the point.

When Optimization Breaks the World

This isn’t just a digital issue—it plays out in real life. Take Waze. Acquired by Google in 2013, the navigation app was initially praised for helping users avoid traffic through real-time, crowdsourced data. But by 2019, the narrative had changed. Smart shortcuts had become everyone’s shortcuts. Suburban streets, sleepy neighborhoods, and steep hills were suddenly flooded. Waze, blind to infrastructure and scale, sent trucks barreling through residential streets, prioritizing time over safety or local well-being.

And the trend hasn’t stopped. In 2024, Le Monde reported that Saint-Montan, a medieval village in southern France with just 1,000 residents, was suddenly overwhelmed by 14,000 vehicles every weekend. Algorithms flagged it as a shortcut to avoid congestion elsewhere—dumping traffic onto a town totally unprepared to handle it.

When algorithms are applied to public space without context, the consequences aren’t just annoying—they’re unsustainable.

Printed and Personal: The Return of the Real Guide

At Le Grand Jeu, highlighting books isn’t just something we do—it’s central to who we are. In recent months, we’ve welcomed three authors who remind us that no app can replace a sharp eye, a distinct voice, and lived experience.

Disek. J’irai graffer chez vous. Paris: Éditions Alternatives, 2025.

Neither a conventional travelogue nor a classic guide, this book lies somewhere in between. French graffiti artist Disek distills a decade of painting missions into one volume, tracing a path through major capitals and forgotten alleys alike. From Bangkok to Lisbon, Marrakech to Mexico City, each destination is a canvas. Travel changes how you paint—and painting changes how you travel.

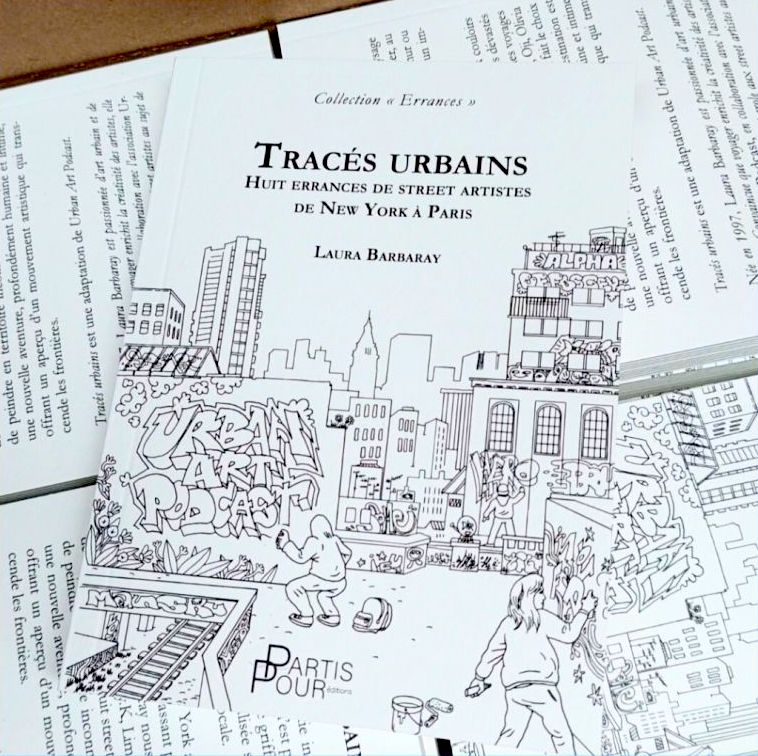

Laura Barbaray. Tracés Urbains: huit errances de street artistes de New York à Paris. Brussels: Partis Pour Éditions, 2025.

What began as a podcast turned into a book in which Laura Barbaray collects the voices of eight street artists, each leaving their mark in eight different cities. More than a travel diary, it’s a layered reminder that street art beats to the rhythm of the everyday: intimate, hyper-local, and global at once.

Giulia BLocal Riva. As Seen in the Streets of Paris. Rome: Self-published, 2025.

Since 2011, Giulia has been documenting street art across Europe via her blog, BLocal. Her latest work is more than a book—it’s a street-savvy, anti-touristy map of Paris, born of real encounters and sustained fieldwork. No filters. No algorithms. Just careful, deliberate exploration.

These three titles show that “travel guide” can mean radically different things. Good news: a disappointing guidebook experience in the past doesn’t mean you’re not a guidebook person. You might just need to find one that speaks your language.

Better Trips Start with Better Books

Éditions Alternatives, a Paris-based publisher, has long championed the potential of printed guides. Their catalog offers dozens of quirky, unexpected French titles—from a Guide de l’archi à Paris (on Parisian architecture), to Guide du Paris vegan (for plant-based explorers), Guide du street art à Paris, guiding you towards the most creative walls, and even Midi Moins Cher, a practical handbook for budget-friendly lunches in the capital.

Turning to curated guides and personal recommendations might feel old-school—but that’s precisely where deeper, richer travel begins. It’s in the intentional choices, the curiosity, the time spent digging.

Over time, these books become more than tools. They’re cultural time capsules, preserving a city’s spirit at a moment in history. A guidebook from 2003 may not help you plan tomorrow’s trip, but it reveals how cities—and our relationships to them—have evolved.

In the 2000s, printed books were essential to the rise of street art culture. Titles like Street Art Stories by Jessica Stewart (Rome: Mondo Bizzarro, 2013), Street Art New York by Jaime Rojo and Steven P. Harrington (Prestel, 2010) and Paris Pochoirs by Samantha Longhi and Benoît Maître (Paris: Alternatives, 2011) defined a movement that arguably peaked in 2017 with Lonely Planet’s Street Art Guide—a turning point, and maybe the end of a certain editorial era.

So next time you pack your bag, don’t just bring your phone. Bring a book. One that reflects someone’s care, time, and attention. One that’s been walked, not just searched.

From Discovery to Recognition—and Back Again

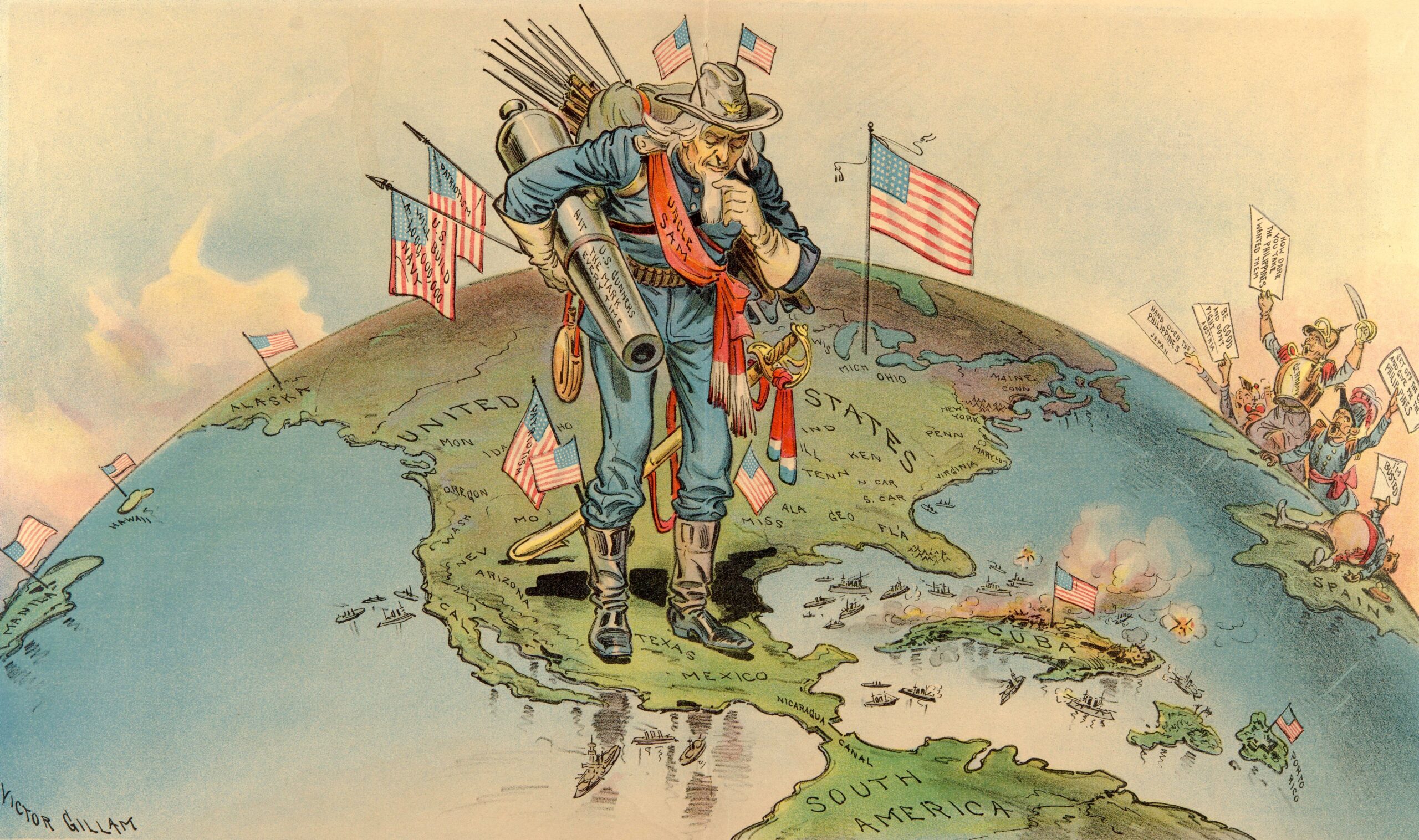

We now have a fairly clear picture of what drives many travel decisions in today’s Western world. But let’s rewind for a moment. Back to the Age of Exploration or the Age of Excavation (of canals like Suez and Panama)—before GPS, before social media, before crowdsourced reviews. Back then, travel meant risk. It meant stepping into the unknown, crossing oceans with no map. The goal was to discover.

The book La manie des Tours du Monde: de Jules Verne aux premiers globetrotters depicts an in-between phase. It’s dedicated to those who first approached a touristic way of travelling: the pioneers of nowadays idea of travelling, but in the pre-algorithm era.

Today? What’s left to discover when every corner is already mapped by Google and every dish already reviewed on Yelp?

If once we traveled to assimilate the unfamiliar, now we often travel to find reflections of ourselves. Walter F. Otto, a German philologist from the last century, in his book Theophany: The Spirit of Ancient Greek Religion warns that modern humans had lost touch with nature, searching only for their own image in everything they encountered.

And maybe that’s exactly what we do when we let algorithms plan our trips: chase confirmation, not transformation. We travel not to meet the unknown—but to validate the familiar, dressed up in foreign clothes.

Isn’t that a paradox? We move to recognize, not to rediscover. We follow the path of least resistance—and call it adventure.

But what if, for once, we allowed ourselves to get lost? To step off the grid, embrace disorientation, and carve out a path that is truly our own?

Maybe then, in retracing those steps, we’ll end up writing a new kind of guidebook. One that’s ours.

Greta Finelli

I wrote this article at the end of my three-month internship at Le Grand Jeu, just before returning to Bologna, where I’m currently studying for a Bachelor’s degree in Philosophy. If you have any feedback, feel free to reach out to me on Instagram. And if you’re curious to read more of my reflections on cultural trends, you can subscribe to my Substack newsletter.