20 years ago, I started my first Balkan trip about almost completely by chance. Back then, for a young, broke Western graffiti writer, the region looked like the holy promised land: paintable on every level, insanely cheap, full of cool and friendly local cats — and, on top of that, the girls were hotter than back home.

But the truth is, what we experienced was the result of a complex post-war situation. A region trying to face the open scars of the Yugoslav wars, one of the most brutal genocides in recent history. Rebuilding a society from scratch. Dealing with the past while handing the future to a generation that almost never was.

Graffiti wasn’t even an issue at the time — I still remember a cop telling me: “We don’t have a law about it, we’re a young nation. So I have to arrest you… and then release you.” One of the most unexpected answers I’ve ever received when asking if painting was allowed.

That kind of freedom — raw, real, almost surreal — in the wild wild East made me want more. I ended up exploring every single country, every possible city. And I never really stopped.

Two decades later, in a more EU-oriented context, I decided to go back. This time to Sarajevo, to see if that original vibe was still there. And to make sure I did my homework, I met with some of the people helping to “defend” the scene — just like Walter, the man of mystery, did in the Tito-era movie.

Taking advantage of Chapters, the exhibition on Balkan hip-hop legend Frenkie at Galerija Manifesto, I sat down with Benjamin Cengic, the director, and Frenkie himself to get an updated Balkan perspective.

Boxir (BO): Hi guys, great to hear from you. Let’s make this playful for our readers. Benjamin, can you introduce Frenkie? And vice versa, Frenkie, can you introduce Galerija Manifesto? Then both of you, can you explain your roles and contributions to the local scene?

Benjamin Cengic (BC): When I was growing up, Frenkie was definitely one of the biggest influences I had. I was listening to his music and was fascinated by his graffiti. For me, he was one of the father figures of graffiti in Bosnia and Herzegovina. When he moved to Sarajevo, we somehow met and started painting together, and that grew into a friendship.

Frenkie (F): Benjamin is a great friend and graffiti artist who I have known for a long time. He is a very important part of our local scene because he is the founder of the Fasada festival and the Manifesto gallery. We all know that Adna is the real boss of the gallery and Benjo is like an underboss who is always on the phone 🙂 In a short time Manifesto became an iconic place for art, so when I was thinking about my first exhibition, it was logical to do it with them.

BO: Let’s talk about Chapters. The show tracing Frenkie’s career has been on display recently. Can you tell us more about the concept and the impact it had? The exhibition touched both on his rap and graffiti sides. Do you think that combination helps reach a broader audience — especially for graffiti culture? as someone said “After all, music soothes even the savage beast.”

F: To be honest I didn’t think about reach and stuff, the idea was like you said to celebrate my 20 year anniversary in music and graffiti. For me both artforms are intertwined and it’s hard to see where one ends and the other begins. It started with graffiti but then music came in and became huge. Although there were some periods where I did music professionally I never stopped loving, following and being part of graffiti. Somehow today graffiti took over and some young kids on the internet know me more like the graffiti guy and not the rapper, which I thought will never happen. Today I follow my good feeling so when I feel like painting I do that, and when inspiration for a new song hits me I write. For me the exhibition was also something new, stepping out of my comfort zone, and it was funny how on opening night I felt stage fright like before a concert. In the end I think everything went perfect, we had a full house, and working with Adna and Benjo was a great experience. We are hoping to bring the exhibition to other cities in Bosnia but also Balkan, because it also carries a lot of Balkan history.

BC: Well, we really wanted to represent the 20 years of Frenkie’s work and presence. Both graffiti and rap are elements of Hip Hop culture and he is a person who was really dedicated to both in the past. We didn’t think about it, but I believe it would be impossible to show him in any other manner. It is like two sides of one coin. When it comes to the impact; I am pretty much sure that his rapper side played a bigger role and that it attracted more people. Graffiti is and always will be an underground subculture, while its sibling (rap) is quite broader and has given Frenkie a lot of fame. He is mainly known as a rapper in our society and with that role he helped in the development of the graffiti scene, as well as its affirmation within the government, corporate world, etc.

BO: Now let’s zoom in on the graffiti scene. I’ve always loved that quote describing former Yugoslavia: “6 republics, 5 nationalities, 4 languages, 3 religions, 2 alphabets and only one Tito.” I find a parallel in graffiti: one common subculture that can work as an eternal ground of unity.

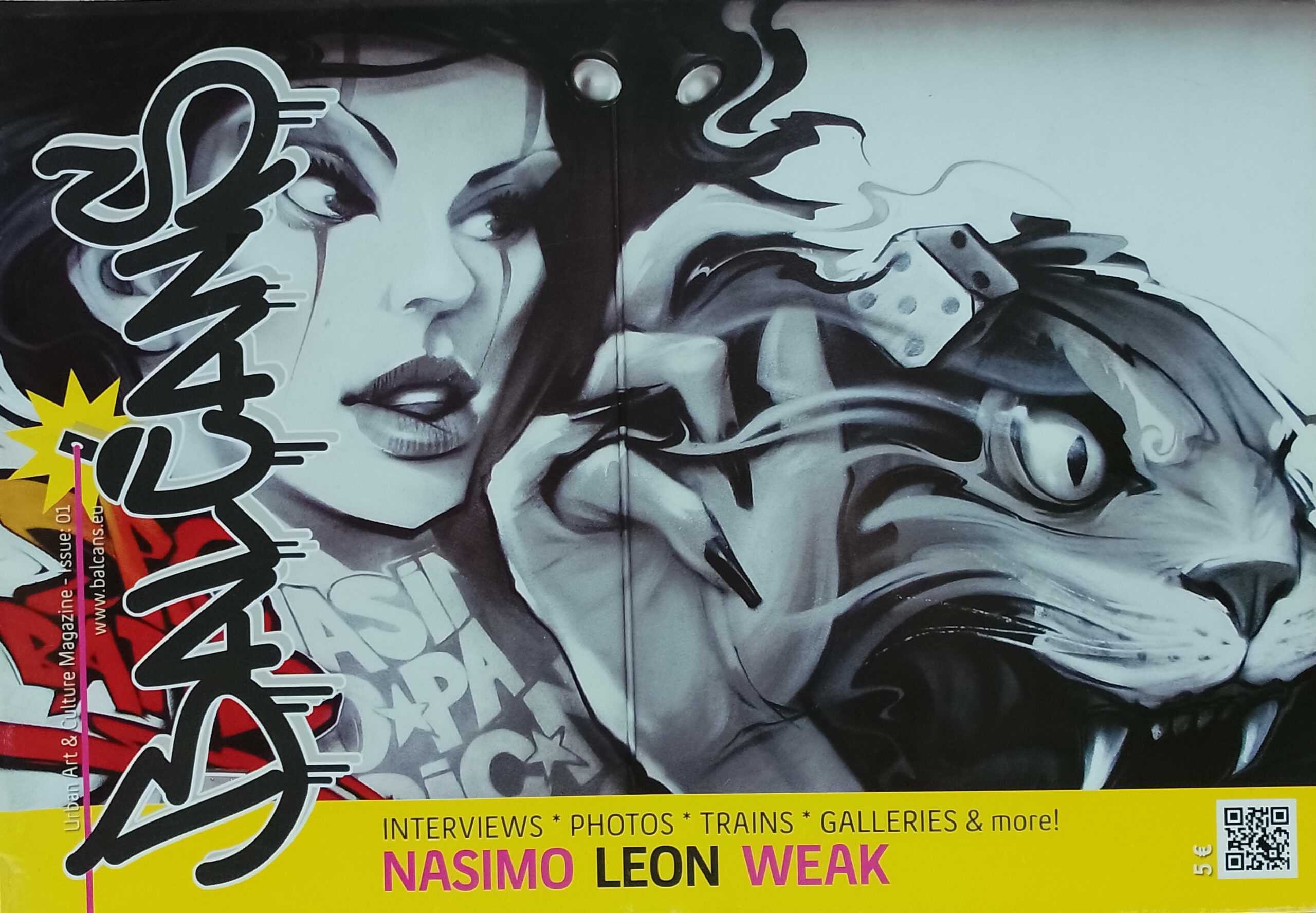

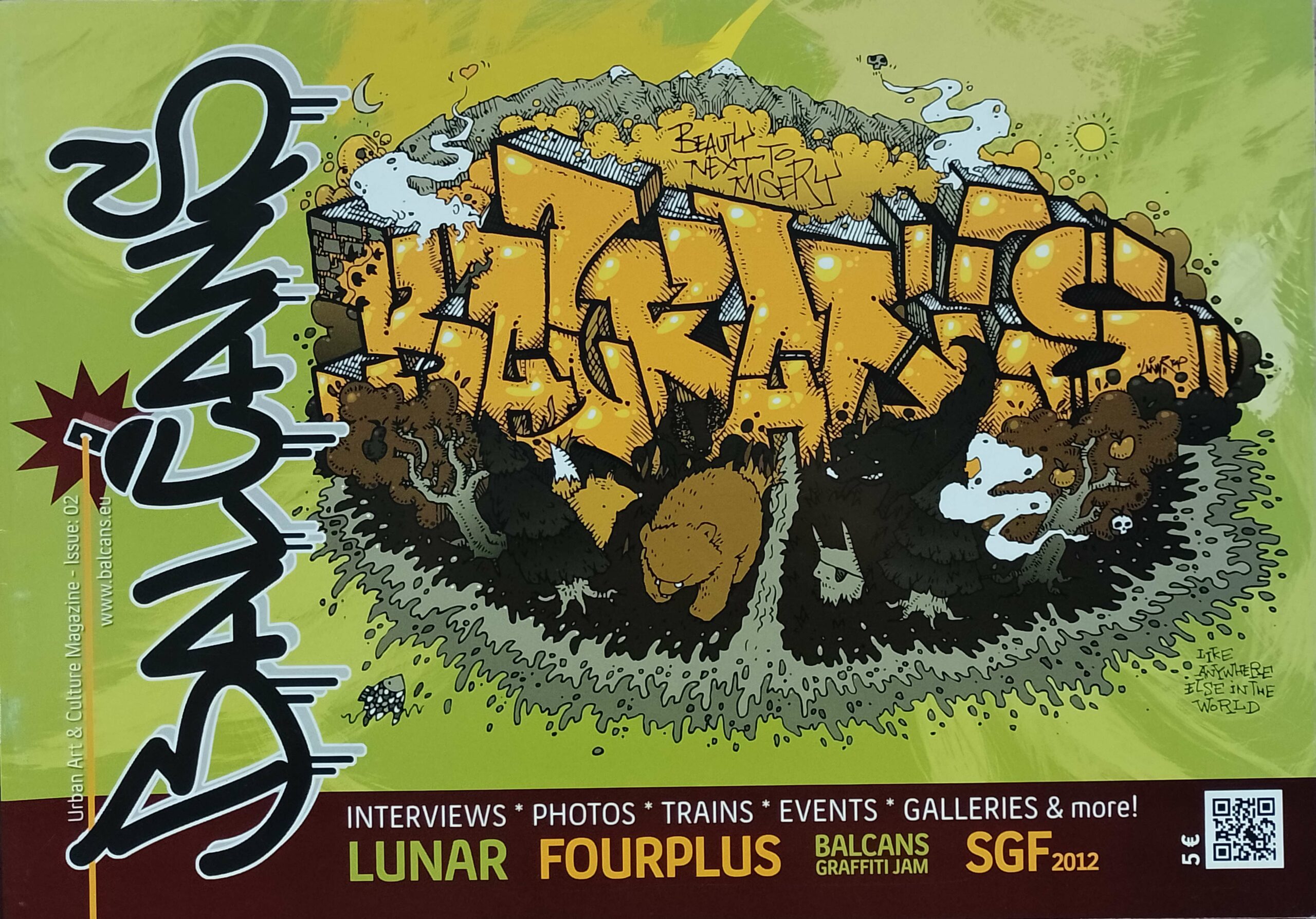

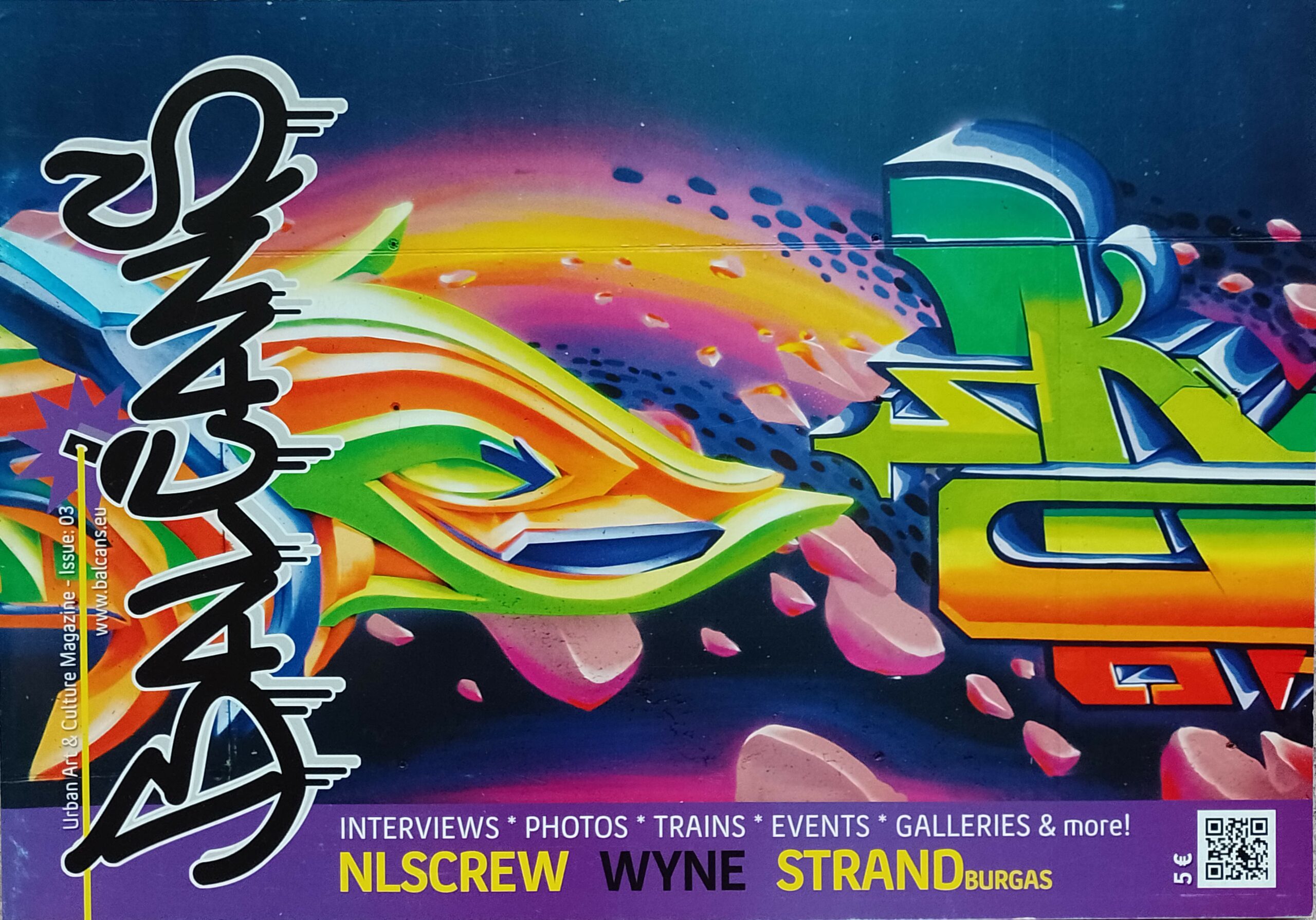

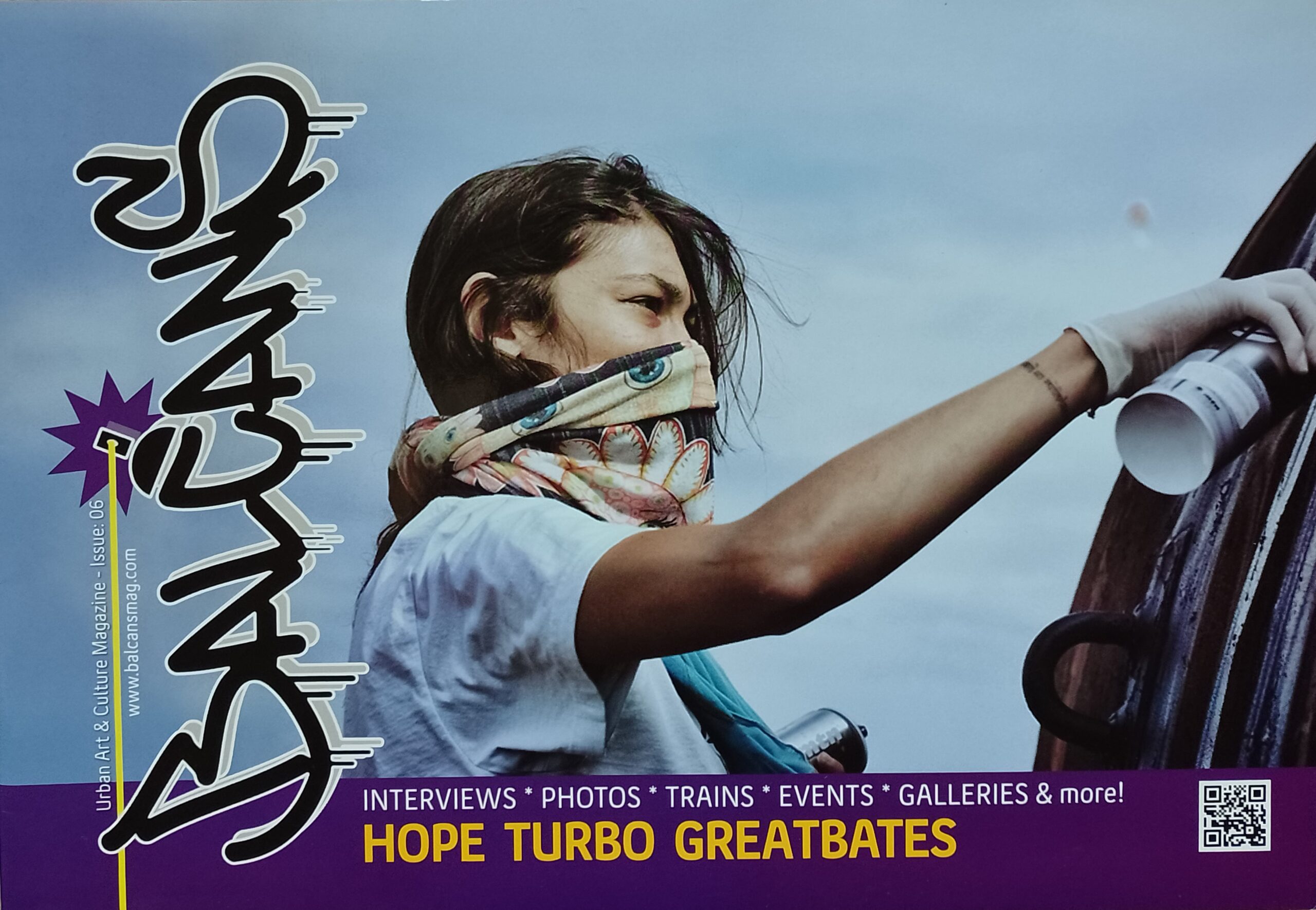

How do you see the connections between different national scenes today? We all know regional icons like Lunar — a true godfather figure — or projects like Balcans Magazine, which aimed to spotlight the whole area. But do you think we can talk about a real Balkan scene, or is it more a constellation of separate scenes? And is it important to keep that sense of unity alive?

F: I always saw it as one scene. That came mostly through music, because although politicians want to separate us we are more similar. The language is basically the same with some slight dialects, but we perfectly understand each other. As a musician I always thought it’s better to have a market of 20 million people than 3 million. And that mindset applies also to the graffiti scene. Of course some locals are better connected but we have numerous festivals which bring people together and collaborate. The Balkan scene is not that big like in Germany or Italy so I think it’s better if we stick together.

BC: I really love that quote. Thank you for bringing it up!

I am probably one of the biggest Yugonostalgics (if that is a word) in the Balkans and have Tito tattooed on my body. I really believe in the spirit of “Brotherhood and unity” and am trying to achieve it through various projects and initiatives.

Unfortunately, I must say that we are talking about separate scenes here. I believe that most of the people involved would be very happy to say that it is one scene, but in order for that scene to exist, we must have more mobility between countries, more “writers benches”, more festivals and things that keep it together. Of course, having no language barrier helps, but the borders still exist and you need some time to travel from one country to another. We have a lot of contacts, a lot of friends and everybody helps each other, and we will definitely continue working on bringing us all together.

BO: Staying in the region, let’s talk about style. I remember visiting Tuzla in 2008 and noticing a strong German influence — probably because many kids fled to Berlin during the war, started painting there, and brought that style back home. That created the foundation for the city’s scene, which is a rare process.

I also remember Zagreb Fever magazine and how it locally upgraded that Berlin base. Can you help us trace the evolution of local styles? How do they align with the latest European trends — especially with the rise of anti-style?

F: You noticed that correctly. I started with graffiti during my life in Germany, so when I came back in 1998. I brought the German flavour with me. I belong to the first generation of writers in Bosnia and most of us are refugees who lived in Germany. You form your definition of style in the early days, so what you see then gets stuck with you. I think that changed today, in the 90s you could recognize a style even by the cities. You had Berlin, then there was Heidelberg, Munchen, Frankfurt, they all had different styles. Today it all grew together and we got a million more new styles. It’s just important to have fun, make yourself free and come home after the painting with a good feeling.

BC: Oh, this is philosophical. I think that nowadays it is hard to talk about style in the same manner as 10 years ago. Of course a lot of influence came from Germany, as you said, many of our writers just came back from refuge and brought it with them, but over years and with the rise of the internet and social media, writers globally were able to see what others do in all the corners of the world. That killed “Berlin” style, and all “city” styles. There are writers in our country who still had or have an influence of sorts, such as Rulof, who continued spreading his influence over younger generations, but that mutated into a different thing. In my case, I still have old works of Rea (Slobo) and Patwo in my head, and when you look at my piece, it is something totally different from what they were doing, but I know what inspired which line and why. I hope what I said makes some sense…

BO: Let’s narrow the focus to Sarajevo. Benjamin, maybe you can walk us through Galerija Manifesto’s work and related public art projects. To me, the city has kept much of the same allure it had 15 years ago. Sure, it’s more touristy now, but the architecture is mostly untouched, and the graffiti at the bottom of each block is still there — no major buffing policy, and people are still painting in the streets.

In that context, what’s the role of institutional dialogue with the city? Sarajevo seems to be one of the closest places we have to the long-gone golden age of graffiti in Europe.

BC: Gallery of Contemporary Arts Manifesto is one of two capital projects of Association Obojena Klapa (Painted Slate). It is a hybrid art space which provides space, opportunities, and help in production, presentation and affirmation of contemporary arts, and uses art as a tool for initiation of dialogue on social and political problems, while working on establishing a contemporary art market in Bosnia and Herzegovina. We organize approximately 11 exhibitions per year, or 80 events (such as talks, workshops, concerts, etc.). The gallery also works through production of new works such as video art, theater plays, performances, installations, etc.

The second capital project which we run is FASADA Festival, an international street art festival which revitalises public space in Sarajevo by turning neglected urban areas into street art galleries. This September, the Festival will have its fifth edition. Apart from the above, we paint murals which are “project based” and commissions and have smaller international projects on the side. And, because it is not enough, we are also a film production company.

From a wider perspective, Bosnia and Herzegovina is the country with the most complicated political system in the world. It is very hard to understand what are the jurisdictions and responsibilities of the City, and what are the jurisdictions and responsibilities of the Municipality. Also, it is a poor country and the graffiti here started in the late 90s. It is still fresh in terms of Bosnian reactivity. That being said, the budget for cleaning graffiti doesn’t exist in the governmental institutions, and even if somebody really wanted to make it, they wouldn’t be able to agree whose responsibility that would be. They are still trying to stop graffiti, and we all know that is impossible.

From a wider perspective, Bosnia and Herzegovina is the country with the most complicated political system in the world. It is very hard to understand what are the jurisdictions and responsibilities of the City, and what are the jurisdictions and responsibilities of the Municipality. Also, it is a poor country and the graffiti here started in the late 90s. It is still fresh in terms of Bosnian reactivity. That being said, the budget for cleaning graffiti doesn’t exist in the governmental institutions, and even if somebody really wanted to make it, they wouldn’t be able to agree whose responsibility that would be. They are still trying to stop graffiti, and we all know that is impossible.

I often get calls about a new piece painted on a tram or some monument and we had many talks with many different government bodies on this “problem”. We don’t have a law that talks about public space in that sense. For the past three years we have been working on it, regarding procedure for obtaining permits for mural painting and the hall of fame establishing. It is still a long way ahead of us and we are consulting the Office for urban planning, Office for preservation of monuments and have even agreed with the Prime Minister of Canton to be awarded with a team of lawyers to help work on it with us.

BO: Back to both of you: what’s next? Any upcoming projects you can reveal or at least give us a sneak peek of?

F: Well it’s summer so I plan to travel and paint as much as possible. Also we have a great festival in Tuzla, it’s called Unity, and this year we have some globally known artists like Baker, Boogie and Hombre, so I’m looking forward to that. There is also the xSTatic festival in Split, and I hope Benjamin invites me to the Fasada festival.

BC: FASADA Festival is starting on 6th of August and finishes on 14th. After that, we continue with our regular Gallery programme. I have a seminar which is a part of one international video art project in Reykjavik on 18th of September and a seminar in Jordan with The Festival Academy on 21st of September. And after those, we must paint a few murals and continue working on other projects while starting to fund-raise for the next year.

BO: Thanks a lot for sharing your insights with us. If you’d like to send a shout-out or give a tip to anyone planning a visit to Sarajevo or the Balkans — like a good place for cevapcici (always a win) — now’s your chance!

F: If you come to Tuzla make sure you visit Limenka, that’s the place to be.

BC: Come to Manifesto! You get to see some amazing art and get personalized tips for the best food and leisure in Sarajevo!